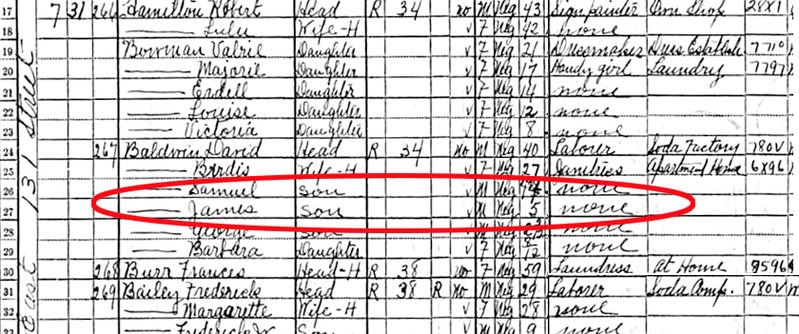

I haven't added this yet to my Harlem Map, i.e. primary documents images of the addresses of where various Harlem luminaries lived. This one is of James Baldwin.

from wikipedia:

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – November 30, 1987) was an American novelist, writer, playwright, poet, essayist, and civil rights activist.

Most of Baldwin's work deals with racial and sexual issues in the mid-20th century United States. His novels are notable for the personal way in which they explore questions of identity as well as for the way in which they mine complex social and psychological pressures related to being black and homosexual well before the social, cultural or political equality of these groups could be assumed.[1]

Baldwin was born in 1924, the first of his mother's nine children.[2] He never met his biological father and may never have even known the man's identity.[3] Instead, he considered his stepfather, David Baldwin, as his father figure. David, a factory worker and a store-front preacher, was allegedly very cruel at home.[4] While his father opposed his literary aspirations,[5] Baldwin found support from a teacher as well from the mayor of New York City, Fiorello H. LaGuardia. At age 14, Baldwin joined the small Fireside Pentecostal Church in Harlem. After he graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, he moved to Greenwich Village, where he concentrated more on his literary career.

One source of support came from an admired older writer Richard Wright, whom he called "the greatest black writer in the world for me." Wright and Baldwin became friends for a short time and Wright helped him to secure the Eugene F. Saxon Memorial Award. Baldwin titled a collection of essays Notes of a Native Son, in clear reference to Wright's novel Native Son.[citation needed] However, Baldwin's 1949 essay "Everybody's Protest Novel" ended the two authors' friendship[6] because Baldwin asserted that Wright's novel Native Son, like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, lacked credible characters and psychological complexity. However, during an interview with Julius Lester, [7] Baldwin explained that his adoration for Wright remained: "I knew Richard and I loved him. I was not attacking him; I was trying to clarify something for myself."

Another major influence on Baldwin's life was the African-American painter Beauford Delaney. In The Price of the Ticket (1985), Baldwin describes Delaney as "the first living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognized as my teacher and I as his pupil. He became, for me, an example of courage and integrity, humility and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow."

Baldwin was closely befriended with singer, pianist and civil rights activist Nina Simone. Together with Langston Hughes and Lorraine Hansberry, Baldwin is responsible for making Simone aware of the racial inequality at the time and the groups that were forming to fight against this. He also provided her with literary references to expand her knowledge on this point.

Baldwin left to live in Europe for an extended period of time beginning in 1948.[8][9] His first destination was Paris. When Baldwin returned to the United States, he became actively involved in the Civil Rights Movement.[10] He marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. to Washington, D.C.[11] During the early 1980s, Baldwin was on the faculty of the Five Colleges in Western Massachusetts. While there, he mentored Mount Holyoke College future playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2002. Baldwin did not remain in the United States long, however, and he was a repeated expatriate for the rest of his life, spending long stints in Istanbul, Turkey[12] and in St.-Paul-de-Vence in Southern France, where he died of esophageal cancer in 1987 at the age of 63.

In 1953, Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, an autobiographical bildungsroman, was published. Baldwin's first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son, appeared two years after. Baldwin continued to experiment with literary forms throughout his career, publishing poetry and plays as well as the fiction and essays for which he was known.

Baldwin's second novel, Giovanni's Room, stirred controversy when it was first published in 1956 due to its explicit homoerotic content.[13] Baldwin was again resisting labels with the publication of this work:[14] despite the reading public's expectations that he would publish works dealing with the African American experience, Giovanni's Room is exclusively about white characters.[15] Baldwin's next two novels, Another Country and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, are sprawling, experimental works[citation needed] dealing with black and white characters and with heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual characters.[citation needed] These novels struggle to contain the turbulence of the 1960s:[citation needed] they are saturated with a sense of violent unrest and outrage.[citation needed]

Baldwin's lengthy essay Down at the Cross (frequently called The Fire Next Time after the title of the book in which it was published)[citation needed] similarly showed the seething discontent of the 1960s in novel form. The essay was originally published in two oversized issues of The New Yorker and landed Baldwin on the cover of Time magazine in 1963 while Baldwin was touring the South speaking about the restive Civil Rights movement. The essay talked about the uneasy relationship between Christianity and the burgeoning Black Muslim movement. Baldwin's next book-length essay, No Name in the Street, also discussed his own experience in the context of the later 1960s, specifically the assassinations of three of his personal friends: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Baldwin's writings of the 1970s and 1980s have been largely overlooked by critics. The assassinations of black leaders in the 1960s as well as Eldridge Cleaver's vicious homophobic attack on Baldwin in Soul on Ice, along with his return to southern France, contributed to the sense that he was not in touch with his readership. Always true to his own convictions rather than to the tastes of others, Baldwin continued to write what he wanted to write. His two novels written in the 1970s, If Beale Street Could Talk and Just Above My Head, placed a strong emphasis on the importance of black families, and he concluded his career by publishing a volume of poetry, Jimmy's Blues, as well as another book-length essay, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, which was an extended meditation inspired by the Atlanta Child Murders of the early 1980s.

Baldwin's influence on other writers has been profound: Toni Morrison edited the Library of America editions of Baldwin's fiction and essays, and a recent collection of critical essays links these two writers.

In 1987, Kevin Brown, a photo-journalist from Baltimore, MD founded the National James Baldwin Literary Society. The group organizes free public events celebrating Baldwin's life and legacy.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment