Saturday, March 1, 2008

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

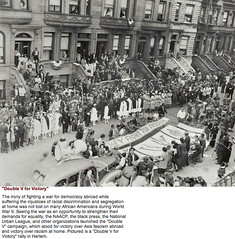

The Double V For Victory

pseudo-intellectualism

One of the many things I learned in reading Striver's Row was the pressure to end some of the humiliations of segregation while Black America's was enlisted to defeat fascism abroad. I was aware of the struggles of the Tuskegee Airmen, but that was tame compared to some of the actual incidents of race wars in southern bootcamps. Above is a picture taken in 1942 on 119th Street. I found at the inmotionaame site Here is a link to a larger image of that site with more background information

Posted by David Ballela at 9:23 AM 0 comments

Labels: harlem, military, tuskegee airmen

Sunday, February 24, 2008

Black History Coloring Pages: Tuskegee Airmen And Black Soldiers

Posted by David Ballela at 1:13 PM 0 comments

Labels: coloring pages, military, tuskegee airmen

Tuskegee Airmen 5

This scene is based on a true life episode where Eleanor Roosevelt makes a special request to fly with one of the Tuskegee pilots to show her faith in their ability

This is mentioned in a history from african americans.com

The controversial decision to establish a training school for African American pilots at the Tuskegee Institute took place on January 16, 1940.

The first all-African American flying unit in the U.S. military, Tuskegee Airmen served during World War II. The squadron was commissioned by the War Department under increased pressure from the NAACP and other organizations seeking to provide opportunities for African Americans in the armed forces. Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr.commanded the Tuskegee Airmens first graduating class. They flew over fifteen hundred missions and destroyed hundreds of enemy aircrafts without ever losing a bomber to hostile fire.

In the face of strong resistance from the military establishment and most officials in the War Department, a relentless effort was carried on by a number of Black organizations and individuals, including sympathetic Whites, to persuade the government to accept Blacks for training by the Air Corps in military aviation. After considerable debate on the subject, the government agreed to establish a program in which African American applicants would be trained in all aspects of military aviation and sent into combat as a segregated unit.

In January 1941, under the direction of the NAACP, a Howard University student, Yancey Williams, filed suit against the War Department to compel his admission to a pilot training center. Almost immediately following the filing of the suit, the War Department under pressure from northern congressmen, and with an order from the Commander-in-Chief, Franklin Roosevelt, announced that it would establish an aviation unit near Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, in cooperation with the institute for the training of Negro pilots for the Army. This unit was to be called the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

The First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, was a strong supporter of the Tuskegee Airmen. She even "inspected the troops" and took a ride with a recent graduate. The first pilot class, completed the training and received their wings on March 7, 1942. The five graduates were: Captain Benjamin O. Davis, 2nd Lieutenant Lemuel R. Custis, 2nd Lieutenant Charles DeBow, 2nd Lieutenant George S. Roberts, and 2nd Lieutenant Mac Ross. The Red Tails Enter Combat The Tuskegee Airmen we nick-named "Red Tails" because of the distinctive red paint on their tails. Airplanes in Tuskegee, Alabama where the group trained were painted with red markings to identify students. When the unit moved to North Africa, replacement aircraft were often bare metal with no paint except for basic identification numbers. It was decided that the colors of the trainer aircraft of Tuskegee would carry over into combat. A simple "A" on the side of the fuselage would designate the 99th Pursuit Squadron, "B" the 100th, "C" the 301st, and "D" for the 302nd. The Airmen had an illustrious record in combat. Over Italy in 1944, Lt. Gwynne Pierson, Lt. Windell Pruitt and four other Tuskegee Airmen, flying P-47s, attacked a German Destroyer (TA-27) in Trieste Harbor. Accurate machine gun fire hit the powder magazine and sank the ship. Thus Pierson and Pruitt are credited with the destruction of an enemy ship using only machine gun fire. Captain Charles B. Hallwas credited as the first African American to shoot down an enemy aircraft. The 450 Tuskegee Airmen assigned to the African/European Theater flew 1578 missions - 15,553 combat sorties while fighting the Germans, both in North Africa and Italy; the unequaled record of not having lost a single bomber, while they were escorting, due to enemy aircraft action. Bomber crews saw the "Red Tails" as a welcome sight. The contributions of the 477th Bombardment Group and their struggle to achieve parity and recognition as competent military professionals, leading to the War Department's evaluation of it's racial policies and the ultimate desegregation of the military. A total of 926 pilots graduated from Tuskegee Army Flying School over the years. Class 46-C was the last class to finish training at the school and graduated on June 29, 1946. Shortly thereafter the "Tuskegee Experience" ended with the closing of Tuskegee Army Air Field. Tuskegee set the tone for leadership in the newly formed Air Force. Excellence was expected and results were positive. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.would become a general and command several air wings as well as Air Force bases. He would lead a new generation of African Americans who were professional soldiers and great leaders. Another Tuskegee graduate was Daniel "Chappie" James, Jr., the first USAF African American 4-star general. After he was promoted to 4-star grade on Sept. 1, 1975, James was assigned as Commander in Chief North American Air Defense Command and Aerospace Defense Command, a position he held until his retirement on Feb. 1, 1978. He died 24 days later. Chappie served in WWII as well as the wars in Korean and Vietnam.

Posted by David Ballela at 12:53 PM 0 comments

Labels: eleanor roosevelt, military, tuskegee airmen

Tuskegee Airmen 4

While on a training mission one of the pilots' planes exhibits trouble and is forced to make an emergency landing. He (played by Malcolm Jamal Warner) lands amidst an all black chain gang. The prisoners and guards look on in disbelief at the site of a black airmen. For the prisoners it is a vision of pride.

Posted by David Ballela at 12:40 PM 0 comments

Labels: military, tuskegee airmen

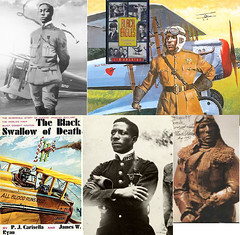

Tuskegee Airmen 3

In this scene the airmens' black instructor exposes their ingrained inferiority complex

as they assume he had no real combat experience. In truth he flew in World Wat One for the Canadians, just like the real life Eugene Bullard flew for the French

Posted by David Ballela at 12:32 PM 0 comments

Labels: military, tuskegee airmen

Tuskegee Airmen 2

In this clip the airmen are forced to change to segregated cars during their train trip once they cross into a southern state. They experience the indignity of viewing German prisoners of war having better accommodations.

Posted by David Ballela at 12:19 PM 0 comments

Labels: civil rights, military, tuskegee airmen

Tuskegee Airmen 1

from an amazon review with which I agree

This true story of the black flyers who broke the color barrier in the U.S. Air Force during World War II is a well-intentioned film highlighted by an excellent cast. Proud, solemn, Iowa-born Laurence Fishburne and city-kid hipster Cuba Gooding Jr. are among the hopefuls who meet en route to Tuskegee Air Force Base, where they are among the recruits for an "experimental" program to "prove" the abilities of the black man in the U.S. armed services. Fighting prejudice from racist officers and government officials and held to a consistently higher level of performance than their white counterparts, these men prove themselves in training and in combat, many of them dying for their country in the process. Andre Braugher costars as a West Point graduate who takes charge of the unit in Africa and in Italy (where it's christened the 332nd). The film is rousing, if slow starting and episodic, but it's periodically grounded by a host of war movie clichés, notably the calculated demise of practically every trainee introduced in the opening scenes (ironic given the 332nd's real-life combat record--high casualties for the enemy, low casualties among themselves, and no losses among the bombers they escorted). Ultimately the Emmy-nominated performances by moral backbone Fishburne and the dedicated Braugher and the energy and cocky confidence of Gooding give their battles both on and off the battlefield the sweet taste of victory.

In this opening clip the new recruits meet aboard a train headed south to Tuskegee.

Cuba Gooding's character, A-Train, declares his origins on 131st Street and Lenox in Harlem. A real life Tuskegee Airmen, Dabney Montgomery from Harlem, was mentioned in a previous posting

Posted by David Ballela at 11:56 AM 0 comments

Labels: military, tuskegee airmen

Monday, February 11, 2008

Dabney Montgomery

Harlem Activist Remembers Slain Civil Rights Hero, interview by -Cheryl Wills

ny1.com, February 11, 2008

NY1 celebrates Black History Month with a week-long salute to the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King and those who are working to keep his dream alive. NY1’s Cheryl Wills filed the following report. At 84, Harlem resident Dabney Montgomery is both living Dr. Martin Luther King's dream and, 40 years after his death, working to keep it alive. He knew King as a student years before the civil rights leader became famous. One of his few mementos is his 50-year-old address book, which bears King's Atlanta address. The two even shared a godmother, making them like brothers. "He could sit down and talk with you or anyone, and you could see that this young man is going to make a mark – somewhere,” says Montgomery. Together, the two would make quite a mark during the civil rights movement. For five days and four terrifying nights in 1965, Montgomery was one of King's personal bodyguards during the third Selma to Montgomery March. He says he was prepared to die to ensure King's safety along state Highway 80. "if we saw anyone pulling a knife or gun out, to go to him, push him to the ground and fall on top of him,” he says. Devastated after King's death in 1968, the Alabama-born activist proved that he was down but not out. He settled into Harlem where he became a community activist, inspiring young people by joining grass roots efforts. He loved the protest march,” says Montgomery’s wife Amelia Montgomery. “He would sacrifice everything to go." And Montgomery also became a leader and historian at the oldest black church in New York: Mother AME Zion. "He's always been one to motive, always been one to inspire," says author and activist Yvonne Davis. Still, that's just the half of Montgomery's story. He is a proud veteran of the Tuskegee Airmen – a group of African American pilots who flew with distinction during World War II. He has received dozens of honors. He met President Bush and received the congressional gold medal. He has been featured in a number of documentaries like this one called "Flying for Freedom: untold stories of the Tuskegee Airmen." And as one of the survivors of both WWII and the civil rights movements, Montgomery says he still lives by King's philosophy. "Don't let fear prevent you from doing anything that's positive,” he says. “Go ahead and do it!"

Posted by David Ballela at 5:52 PM 2 comments

Labels: dabney montgomery, military, ny1 community highlights, tuskegee airmen

Wednesday, February 6, 2008

Brothers In Arms 2: The Story Of The 761st Tank Battalion

from 4/22/07 from pseudo-intellectualism Many of the images in the Brothers In Arms' slide show posting of 4/6/07 came from the drawings of Sgt. Charles King, a gifted artist who had trained at the Art Institute of Chicago (above). His tragic story: http://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,457332,00.html

from 4/22/07 from pseudo-intellectualism Many of the images in the Brothers In Arms' slide show posting of 4/6/07 came from the drawings of Sgt. Charles King, a gifted artist who had trained at the Art Institute of Chicago (above). His tragic story: http://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,457332,00.html

FROM FATHER TO SON

Last Words to Live By

By Dana Canedy, January 2, 2007

First Sgt. Charles M. King is remembered by his fiancée, Dana Canedy, an editor at The New York Times.

He drew pictures of himself with angel wings. He left a set of his dog tags on a nightstand in my Manhattan apartment. He bought a tiny blue sweat suit for our baby to wear home from the hospital. Then he began to write what would become a 200-page journal for our son, in case he did not make it back from the desert in Iraq.

Dear son, Charles wrote on the last page of the journal, "I hope this book is somewhat helpful to you. Please forgive me for the poor handwriting and grammar. I tried to finish this book before I was deployed to Iraq. It has to be something special to you. I've been writing it in the states, Kuwait and Iraq.

The journal will have to speak for Charles now. He was killed Oct. 14 when an improvised explosive device detonated near his armored vehicle in Baghdad. Charles, 48, had been assigned to the Army's First Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment, Fourth Infantry Division, based in Fort Hood, Tex. He was a month from completing his tour of duty.

For our son's first Christmas, Charles had hoped to take him on a carriage ride through Central Park. Instead, Jordan, now 9 months old, and I snuggled under a blanket in a horse-drawn buggy. The driver seemed puzzled about why I was riding alone with a baby and crying on Christmas Day. I told him.

"No charge," he said at the end of the ride, an act of kindness in a city that can magnify loneliness.

On paper, Charles revealed himself in a way he rarely did in person. He thought hard about what to say to a son who would have no memory of him. Even if Jordan will never hear the cadence of his father's voice, he will know the wisdom of his words.

Never be ashamed to cry. No man is too good to get on his knee and humble himself to God. Follow your heart and look for the strength of a woman.

Charles tried to anticipate questions in the years to come. Favorite team? I am a diehard Cleveland Browns fan. Favorite meal? Chicken, fried or baked, candied yams, collard greens and cornbread. Childhood chores? Shoveling snow and cutting grass. First kiss? Eighth grade.

In neat block letters, he wrote about faith and failure, heartache and hope. He offered tips on how to behave on a date and where to hide money on vacation. Rainy days have their pleasures, he noted: Every now and then you get lucky and catch a rainbow.

Charles mailed the book to me in July, after one of his soldiers was killed and he had recovered the body from a tank. The journal was incomplete, but the horror of the young man's death shook Charles so deeply that he wanted to send it even though he had more to say. He finished it when he came home on a two-week leave in August to meet Jordan, then 5 months old. He was so intoxicated by love for his son that he barely slept, instead keeping vigil over the baby.

I can fill in some of the blanks left for Jordan about his father. When we met in my hometown of Radcliff, Ky., near Fort Knox, I did not consider Charles my type at first. He was bashful, a homebody and got his news from television rather than newspapers (heresy, since I'm a New York Times editor).

But he won me over. One day a couple of years ago, I pulled out a list of the traits I wanted in a husband and realized that Charles had almost all of them. He rose early to begin each day with prayers and a list of goals that he ticked off as he accomplished them. He was meticulous, even insisting on doing my ironing because he deemed my wrinkle-removing skills deficient. His rock-hard warrior's body made him appear tough, but he had a tender heart.

He doted on Christina, now 16, his daughter from a marriage that ended in divorce. He made her blush when he showed her a tattoo with her name on his arm. Toward women, he displayed an old-fashioned chivalry, something he expected of our son. Remember who taught you to speak, to walk and to be a gentleman, he wrote to Jordan in his journal. These are your first teachers, my little prince. Protect them, embrace them and always treat them like a queen.

Though as a black man he sometimes felt the sting of discrimination, Charles betrayed no bitterness. It's not fair to judge someone by the color of their skin, where they're raised or their religious beliefs, he wrote. Appreciate people for who they are and learn from their differences.

He had his faults, of course. Charles could be moody, easily wounded and infuriatingly quiet, especially during an argument. And at times, I felt, he put the military ahead of family.

He had enlisted in 1987, drawn by the discipline and challenges. Charles had other options - he was a gifted artist who had trained at the Art Institute of Chicago - but felt fulfilled as a soldier, something I respected but never really understood. He had a chest full of medals and a fierce devotion to his men.

He taught the youngest, barely out of high school, to balance their checkbooks, counseled them about girlfriends and sometimes bailed them out of jail. When he was home in August, I had a baby shower for him. One guest recently reminded me that he had spent much of the evening worrying about his troops back in Iraq.

Charles knew the perils of war. During the months before he went away and the days he returned on leave, we talked often about what might happen. In his journal, he wrote about the loss of fellow soldiers. Still, I could not bear to answer when Charles turned to me one day and asked, "You don't think I'm coming back, do you?" We never said aloud that the fear that he might not return was why we decided to have a child before we planned a wedding, rather than risk never having the chance.

But Charles missed Jordan's birth because he refused to take a leave from Iraq until all of his soldiers had gone home first, a decision that hurt me at first. And he volunteered for the mission on which he died, a military official told his sister, Gail T. King. Although he was not required to join the resupply convoy in Baghdad, he believed that his soldiers needed someone experienced with them. "He would say, 'My boys are out there, I've got to go check on my boys,' " said First Sgt. Arenteanis A. Jenkins, Charles's roommate in Iraq.

In my grief, that decision haunts me. Charles's father faults himself for not begging his son to avoid taking unnecessary risks. But he acknowledges that it would not have made a difference. "He was a born leader," said his father, Charlie J. King. "And he believed what he was doing was right."

Back in April, after a roadside bombing remarkably similar to that which would claim him, Charles wrote about death and duty.

The 18th was a long, solemn night, he wrote in Jordan's journal. We had a memorial for two soldiers who were killed by an improvised explosive device. None of my soldiers went to the memorial. Their excuse was that they didn't want to go because it was depressing. I told them it was selfish of them not to pay their respects to two men who were selfless in giving their lives for their country.

Things may not always be easy or pleasant for you, that's life, but always pay your respects for the way people lived and what they stood for. It's the honorable thing to do.

When Jordan is old enough to ask how his father died, I will tell him of Charles's courage and assure him of Charles's love. And I will try to comfort him with his father's words.

God blessed me above all I could imagine, Charles wrote in the journal. I have no regrets, serving your country is great.

He had tucked a message to me in the front of Jordan's journal. This is the letter every soldier should write, he said. For us, life will move on through Jordan. He will be an extension of us and hopefully everything that we stand for. ... I would like to see him grow up to be a man, but only God knows what the future holds.

Posted by David Ballela at 10:57 AM 0 comments

Labels: military

Brothers In Arms: NY War Stories: 761st Tank Battalion

In the NYC companion edition to "The War" one of the people who is highlighted is William McBurney who was a member of this famed Battalion. The story of the battalion is the focus of an excellent book written by Kareem Abdul Jabbar. Tavis Smiley interviewed him back in 2004.From a previous post with a replacement video (I matched pics with the audio0 I even supplied the transcript to read along

original airdate May 21, 2004

Most know that hoops legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was the kind of player that graces a sport once in a lifetime. What may be a surprise is that he's a student of history, his major at UCLA. As a child, he spent hours exploring Harlem's Schomburg Center. Inspired by a 1992 documentary, Abdul-Jabbar co-authored Brothers in Arms, the storyof World War II's forgotten heroes - the 761st Tank Battalion, one of the first all-Black tank crews.

Kareem Abdul-JabbarTavis: You've been all right, man?

Kareem: I've been fine, thank you.

Tavis: Good. Before I get into this book, one of the things that troubles me to this day, and I've got any number of conversations about these. I don't know if you have had these kinds of conversations, but I find myself in conversations routinely where because African-Americans, according to the polls and surveys and studies are opposed to the war in Iraq. No community is more opposed to the war in Iraq than African-Americans are, and there are a lot of folk who will take those statistics and suggest that black folk are not "patriots," that they're not down with the cause, they're not down with the struggle, they're not patriotic as other Americans are, and my sense is that they feel that way because what these poll numbers suggest, but they don't understand the sacrifice African-Americans have made for years serving in the military. You have any conversations like that?

Kareem: I haven't had very many. No, from what I can see, just from what I've observed, black people are pretty much in the middle. They're supporting both sides of the issue.

Tavis: Yeah. How did your attention get drawn to the 761st specifically?

Kareem: Well, my father was a police officer with one of the gentlemen in the unit. I've known this gentleman since I was like, 8 or 9 years old. He's one of my dad's best friends, and I had no idea that he was a war hero. I didn't find out he was a war hero till 1992. I was in my forties.

Tavis: You'd known him your whole life, but you didn't know he was a war hero?

Kareem: Right. I had no idea and watched a documentary that talked about what they did and how they had to fight for the right to fight for their country and some of what they did, but unfortunately in that documentary, a number of the facts got confused, and it again created more controversy and saw to it that these men did not get their due recognition.

Tavis: I know you've been asked about this before, but it is really a fascinating part of the book, so forgive me in indulging me for asking again, but Jackie Robinson, the Jackie Robinson, was a part of the 761st.

Kareem: Yes, Jackie Robinson was their morale officer. He came over from the Ninth Cavalry, and he was dealing with a court-martial when they got called over to Europe. He had refused to sit in the back of the bus. He was told to do so by a white bus driver and because he resisted, both verbally and threatened to do so physically, they put him up on court-martial charges, and he was dealing with that when the unit got called over to Europe, and so after he beat the charges, he had a choice either to stay in the army and rejoin his unit or to take an honorable discharge, and he had had enough by then.

Tavis: You said morale officer. What did a morale officer do back then?

Kareem: Morale officer is supposed to keep up the esprit de corps, and just they...soldiers want their officers to be intelligent and athletic and capable, and, you know, Jackie was all of that.

Tavis: Yeah, no question. What specifically did the 761st do? They were a tank battalion, obviously, but what role did they play in World War II? What did they do specifically?

Kareem: Well, in World War II, they were--A battalion would be used by any infantry unit that needed it. What happened was after the D-Day invasion, the Allies, when they went up against the front-line German tank units, the Allies really didn't do very well, and by September of 1944, Patton needed trained tankers. The 761st was the only battalion left that had been totally trained and was just sitting around doing nothing, because they were only supposed to be doing it as a public-relations ploy to get black people to support the war effort.

Tavis: I'm glad you said that. I wrote down this quote from Patton, which was stunning to me, the juxtaposition, at least, of these 2 quotes. So Patton, General Patton addressing the troops in 1944, addressing these black troops, 761st, in 1944, says, and I quote, "Everyone has their eyes on you and is expecting great things from you, most of all, your race is looking forward to your success. Don't let them down, and damn you, don't let me down." That's what Patton says in '44 to these African-American troops. Later on, writing in his diary, he says that the men of the 761st gave a very good first impression, "But I had no faith in the inherent fighting ability of their race."

Kareem: That was the same night.

Tavis: That's the same night?

Kareem: He wrote that the same night.

Tavis: Now, that threw me.

Kareem: He said he addressed them today, and then you quoted him.

Tavis: So during the day, he's like, "Don't let me down. Don't let your race down. We're depending on you, rah, rah, rah."

Kareem: Then you see what he really feels.

Tavis: And then, that night, in his own diary, he writes, "I ain't got no faith in these cats, because their race don't know how to represent here."

Kareem: Exactly.

Tavis: So to your earlier point then, I'm gonna leave Patton alone for a second. That's disturbing me, but--I used to like General Patton. He's tricky now to me.

Kareem: Yeah, he is.

Tavis: He's very tricky, but let me ask you, though, whether or not the troops ever found out what Patton really thought of them?

Kareem: Patton wanted them to go out there and do what they needed to do to help his army win, and they did a very good job of that, so he appreciated them on that level, but then at the same time, he saw to it that they didn't get the recognition they deserved. All the paperwork, for example, that people put in to give these guys, to nominate them for honors, got lost in Patton's chain of command somewhere, just disappeared, and it took people working decades later looking back to see to it that they were honored correctly.

Tavis: What's your sense of how they dealt with knowing they were only used because Patton didn't have any other troops left?

Kareem: They knew that it would probably take something like that for them to get a chance, but that's all they wanted was a chance, and they ended up being the best-trained unit that we had. They trained for 2 1/2 years.

Tavis: 'Cause they couldn't fight. All they did was train, so they were the best.

Kareem: They knew everything. They knew all the German equipment, its strengths and weaknesses, and the strengths and weaknesses of the Sherman tank, so when they got out there in the field, they knew how to stay alive, even though they didn't have better equipment.

Tavis: But back to the Jackie Robinson role, at least the role he played earlier on, being their morale officer, though, I can't imagine--maybe you can--I can't imagine knowing that I'm being player-hated on, I'm being mistreated because I'm an African-American. I'm the last one to fight, and you only let me go fight, represent my country 'cause you ain't got nobody else left to go, but then I'm supposed to go out there and be down with America and help us win. That really is the definition to me of patriotism and bravery to do that when you know you only being used because you're black. You're the last thing left.

Kareem: Well, they felt that if they did well, they would prove to America that their bravery and competence went across the board, and it wasn't just in these emergencies when they were needed to fight a very formidable foe.

Tavis: I'm out of time here, unfortunately, but yet, when they came home, they had to still sit in the back of the train, goin' down south, these troops behind...

Kareem: But they came home with an attitude that they could change things, that there was something left to do. I'm sure that what they learned in their military service is what gave them the gumption to go out and make the civil rights movement happen, 'cause it started immediately when these guys got home. All of a sudden, the civil rights movement started, and it didn't stop.

Tavis: Well, it's a great book. 'Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story of the 761st Tank Battalion: World War II's Forgotten Heroes.' No better time now than to read this and be reminded of the contribution that all Americans have made, but certainly, African-Americans as well to the freedoms that we enjoy today. Kareem, always nice to see you, man.

Kareem: Hey, thanks a lot.

Tavis: We'll talk basketball maybe next time.

Kareem: Anytime.

Tavis: All right, we'll do it again.

Posted by David Ballela at 10:55 AM 0 comments

Labels: kareem abdul jabbar, military

Sunday, February 3, 2008

Flyboys

more on the Eugene Bullard topic, from 11/10/07 from pseudo-intellectualism from wikipedia:

Flyboys is a 2006 drama film set during World War I, starring James Franco, Martin Henderson, Jean Reno, Jennifer Decker, David Ellison and Tyler Labine. It was directed by Tony Bill and written by David S. Ward, based on an original screenplay by Phil Sears and Blake Evans

The film follows the enlistment, training and aerial combat service of a group of young Americans who volunteer to become fighter pilots in the Lafayette Escadrille, the 124th air squadron formed by the French in 1916. The squadron consisted entirely of American volunteers who wanted to fly biplanes and fight in the First World War during the early years when the United States remained neutral.

The film was shot on location in the United Kingdom in Spring 2005 . The trench scenes were shot in Hatfield, Hertfordshire, the same location used for Band of Brothers and Saving Private Ryan. The airfield and aerial shots were filmed on and above RAF Halton (near Aylesbury) where hangers, mess rooms and officers quarters were built adjacent to Splash Covert woods. All were removed when filming ended.

The film was financed privately outside the standard Hollywood studio circuit by a group of filmmakers and investors, including producer Dean Devlin and pilot David Ellison, son of Oracle Corp. founder Larry Ellison; both spent more than $60 million of their own money to make and market Flyboys.

The Nieuport 17s featured in the film were built by Airdrome Aeroplanes, an aircraft company based outside of Kansas City, Missouri.

A group of young Americans go to France, for different personal reasons, and volunteer to fight in the French Air Service, the Aéronautique militaire, during World War I prior to America's entrance into the war. During the training period, the film mostly follows their personalities and developments; later, the focus shifts to the art of the aerial dogfight. Themes of revenge and love are also explored. The film ends with an explanation of what happened to each character, as the movie was based on real occurrences.

This film has been widely criticized for its lack of historical accuracy, anachronisms, and prochronisms. Various major details of World War 1 fighter aircraft technology shown in the film were highly inaccurate, even beyond typical Hollywood standards of accuracy. For example, the aircraft engines in the CGI scenes are pictured as not moving. The rotary engines used in early aircraft rotated along with the propeller at the same speed. The anti-aircraft artillery shown in use by the Germans was not of any type used by any side in the First World War, and those that did exist were not nearly as accurate as that shown. In reality, had any of the portrayed flak burst as close as it appeared in the film, the aircraft would have been most likely destroyed.[citations needed] One major point of contention in the film is the wide usage of Fokker Dr.I triplanes. Not only was the Dr.I not in usage at the time the film supposedly took place, when it was used it was not in such a large role, nor was it regularly painted red.In the film, the RMS Aquitania is depicted as a luxury liner, however, in early 1914 she was converted to use as an armed merchant cruiser, and by 1915 had been put into use as a troop transport ship and painted with dazzle style camouflage. Also, one scene describes the Germans as using a new 9mm caliber "Spandau" machine gun, even though no German machine gun was ever produced in 9mm, but rather in 7.92mm.

Posted by David Ballela at 3:37 PM 0 comments

Labels: eugene bullard, military

Lafayette Escadrille

from 11/11/07 from pseudo-intellectualism This is from a really good multi-part WWI documentary on youtube called The Great War In The Air. Notice how there's no mention of Eugene Bullard in this wiki entry:

The Lafayette Escadrille (from the French Escadrille De Lafayette) was a squadron of the French Air Service, the Aéronautique militaire, during World War I composed largely of American volunteer pilots flying fighters.

The squadron was formed in April 1916 as the Escadrille américaine (number 124) in Luxeuil prior to U.S. entry into the war. Dr. Edmund L. Gros, director of the American Ambulance Service, and Norman Prince, an American expatriate already flying for France, led the efforts to persuade the French government of the value of a volunteer American air unit fighting for France. The aim was to have their efforts recognized by the American public and thus, it was hoped, the resulting publicity would rouse interest in abandoning neutrality and joining the fight.

(In fact higher numbers of American volunteers served with the Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force during the conflict.)

The squadron was quickly moved to Bar-le-Duc, closer to the front. A German objection filed with the U.S. government led to the name change in December over the actions of a supposed neutral nation. The original name implied that the U.S. was allied to France when it was in fact neutral like Sweden.

The planes, their mechanics, and the uniforms were French, as was the commander, Captain Georges Thenault. Five French pilots were also on the roster, serving at various times. Raoul Lufbery, a French-born American citizen, became the squadron's first, and ultimately their highest claiming, flying ace with 16 confirmed victories before his squadron was transferred to the US Air Services.

The first major action seen by the squadron was at the Battle of Verdun, being posted to the front in May 1916 until September 1916, when the unit moved to 7 Army area at Luxeuil. The squadron, flying the Nieuport scout, suffered heavy losses, but its core group of 38 was rapidly replenished by other Americans arriving from overseas. So many volunteered that a "Lafayette Flying Corps" was formed in part to take the overflow, many Americans thereafter serving with other French air units. Altogether, 265 American volunteers served in the Corps. Although not formally part of the Lafayette Escadrille, other Americans such as Michigan's Fred Zinn, who was a pioneer of aerial photography, fought as part of the French Foreign Legion and later the French Aéronautique militaire.

63 Corps members died during the war, 51 of them in action against the enemy. The Corps is credited with 159 enemy kills. It amassed 31 Croix de guerre, and its pilots were awarded seven Médailles militaires and four Légions d'honneur. 11 of its members were deemed flying aces, claiming 5 air kills or more. The core squadron suffered 9 losses and was credited with 41 victories.

The Escadrille had a reputation for daring, recklessness, and a party atmosphere.] Two lion cubs, named "Whiskey" and "Soda", were made squadron mascots.

Lufbery got into trouble for hitting an officer who was unwise enough to lay hands on him during an argument. He was rescued from jail by his squadron mates. He was a man after the heart of French ace Charles Nungesser who came calling on the escadrille during one of his convalescences. He borrowed a Spad and shot down another German plane even though he was officially grounded.

On February 8, 1918, the squadron was transferred to the United States Army Air Service as the 103rd Pursuit Squadron. For a brief period it retained its French planes and mechanics. Most of its veteran members were set to work training newly-arrived American pilots. The 103rd PS claimed a further 49 kills up until November 1918.

Members

* Hobey Baker

* Clyde Balsley

* Courtney Campbell

* Victor Chapman (1890-1916) The first American aviator to be killed in World War I

* Elliot C. Cowdin

* Marsh Corbitt (1890-1988) Ace

* Edmond Genet The first American flier to die after the United States declared war against Germany

* Bert Hall (1885-1948) Film Director, Actor, Writer & Lieutenant. Wrote two books about being a "Flyboy" in the Lafayette Escadrille.

* James Norman Hall (1887-1951), co-author of Mutiny on the Bounty

* Willis Haviland

* Walter Lovell

* Raoul Lufbery (1885-1918), an ace who died in combat

* Didier Masson (1886-1950)

* James R. McConnell

* Edwin C. "Ted" Parsons

* Norman Prince (1887-1916), Founder and ace

* Frederick H. Prince, Jr. (1885-1963)

* Kiffin Rockwell

* William Thaw

* Gill Robb Wilson

* A statue by the sculptor Gutzon Borglum titled The Aviator (1919) was erected on the grounds of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia in the memory of James R. McConnell, a member of the squadron who was killed during the War. Before he was killed McConnell wrote a first-hand account of the war, Flying in France, that gives the reader invaluable insight into the war in France from 1915 until his death in 1917. Letters added to the end of the book include an account of McConnell's demise.

The story of the Lafayette Escadrille has been adapted into two films: Lafayette Escadrille (1958), a William A. Wellman movie starring Tab Hunter, and Flyboys (2006), directed by Tony Bill and starring James Franco. The Lafayette Escadrille also appears in "Attack of the Hawkmen," an episode of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles in which Indy is temporarily assigned to the group as an aerial reconnaissance photographer.

The exploits of the Lafayette Escadrille are also captured in several works of historical fiction including: To the Last Man by Jeffrey Shaara,Valiant Volunteers by Terry L. Johnson (2005), and An Ace Minus One by Timothy Morrisroe (2006).

Follow up: an anonymous comment was left on the original posting in response to my

cynicism of why Eugene Bullard was not listed

"Notice how there's no mention of Eugene Bullard in this wiki entry:"

That's probably a good thing as Eugene Bullard was *never* in the Lafayette Escadrille (N.124 nor Spa.124). He was in the larger organization of Americans who flew for the French called the Lafayette Flying Corps. He flew with Spa.93 (The Lafayette Flying *Corps*) following his transfer from a French Foreign Legion Infantry unit. After fewer than 50 missions, Bullard ran into trouble with his superiors and was transferred back to the infantry. By first-hand accounts, Bullard was well-liked by his fellow fliers. You can find all the info you'd like in this book:Nordhoff, Charles and James Norman Hall. The Lafayette Flying Corps. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920. One of these guys (Hall) was in the Escadrille, the other (Nordhoff) flew in the Corps. I know that this contradicts the movie "Flyboys", but, c'est la vie.

Posted by David Ballela at 1:42 PM 1 comments

Labels: eugene bullard, military

Eugene Bullard In Harlem

from 5/23/07 from pseudo-intellectualism Over a year ago I did a post on the Peekskill Concert Riots in 1949. One of the people involved was Eugene Bullard. I had found a picture of him on Howard Fast's site (famed writer and author of Peekskill USA). It showed Bullard being beaten by State Police for probably no reason other than these: he was a supporter of Paul Robeson and an attendee of the concert and because he was black. I had never heard of him, but the picture mentioned he was a war hero. I looked him up and found that he had flown for the Lafayette Escadrille!

from 5/23/07 from pseudo-intellectualism Over a year ago I did a post on the Peekskill Concert Riots in 1949. One of the people involved was Eugene Bullard. I had found a picture of him on Howard Fast's site (famed writer and author of Peekskill USA). It showed Bullard being beaten by State Police for probably no reason other than these: he was a supporter of Paul Robeson and an attendee of the concert and because he was black. I had never heard of him, but the picture mentioned he was a war hero. I looked him up and found that he had flown for the Lafayette Escadrille!

I recently watched the DVD of Flyboys. Despite poor reviews I found the film had redeeming qualities. It seemed that the character of the black pilot Skinner was based on Bullard. Research bore that out. I also found that Bullard lived in Harlem in his later years at 80 East 116th Street. Amazingly, with all the renovation that neighborhood has undergone the building is still there. That's a picture of it above. I would think the building deserves a plaque.

Posted by David Ballela at 12:52 PM 1 comments

Labels: eugene bullard, harlem, military

Eugene Bullard 3

from 11/10/07: The story of Eugene Bullard, whose WWI experiences were used as a basis for Flyboys

Posted by David Ballela at 12:49 PM 0 comments

Labels: eugene bullard, military

Eugene Bullard: On The Job

"Eugene Bullard was the world's first black combat aviator, flying in French squadrons during World War I (1917-18). Before he became a pilot he served in the French infantry and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Born in a three-room house in Columbus, Eugene James (Jacques) Bullard was the seventh child of Josephine Thomas and William O. Bullard. Bullard's parents, married in Stewart County in 1882, had Creek Indian as well as African American ancestry. William Bullard was born a slave; his parents were the property of Wiley Bullard, a planter in Stewart County. In the early 1890s William Bullard moved to Columbus, where he worked for W. C. Bradley, a rising cotton merchant.

The young Bullard attended the Twenty-eighth Street School from 1901 to 1906. Although his education was minimal, he nonetheless learned to read, one of the keys to his later successes. With his older sister and brothers, Bullard absorbed his father's conviction that African Americans must maintain dignity and self-respect in the face of the prejudice of a white majority determined to "keep blacks in their place" at the bottom of society. Shaken by the near lynching of his father in 1903 and seeking adventure in the world beyond Columbus, he ran away from home in 1906. In Atlanta he joined a group of gypsies (an English clan known by the surname Stanley) and traveled with them throughout rural Georgia, tending and learning to race their horses. The Stanleys brought to his attention that the racial color line did not exist in England. Disheartened that the gypsies were not soon returning home, Bullard left them at their camp in Bronwood in 1909 and found work and patronage with the Zachariah Turner family of Dawson. Friendly and hard working as a stable boy, Bullard won the affection of the Turners, who allowed him to ride as their jockey in horse races at the Terrell County Fair in 1911.

Despite his relationship with the Turners, Bullard was still affronted by racism and he resolved to leave the United States for Great Britain. He did so as a stowaway on a German merchant ship, the Marta Russ, which departed Norfolk, Virginia, on March 4, 1912, bound for Aberdeen, Scotland. In 1912-14, Bullard performed in a vaudeville troupe and earned money as a prizefighter in Great Britain and elsewhere in Western Europe. He appeared in Paris for the first time at a boxing match in November 1913.

At the beginning of World War I, Bullard joined the French army, serving in the Moroccan Division of the 170th Infantry Regiment. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre for his bravery at the Battle of Verdun. Twice wounded and declared unfit for infantry service, he requested assignment to flight training. He amassed a distinguished record in the air, flying twenty missions and downing at least one German plane.Between the world wars he owned and managed nightclubs in the Montmartre section of Paris, where he emerged as a leading personality among such African American entertainers as Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, and Sidney Bechet. In 1923 he married Marcelle Straumann, the daughter of a wealthy Parisian family. The couple had two surviving children, Jacqueline and Lolita, before separating in 1931. In the late 1930s Bullard joined a French government counterintelligence network spying on Germans in Paris. When Nazi Germany conquered France in 1940 Bullard and his daughters escaped to New York City. He worked there in a variety of occupations for the rest of his life."

If you watched the slide show movie that accompanied the 4/19 "Hold The Line" post you would have seen Eugene Bullard being beaten by cretinous Peekskill thugs at the Paul Robeson concert in 1949. I had never heard of Mr. Bullard until then, but then I realized he has a chapter about him in the Scholastic book, "Black Eagles," which I've seen in several classrooms.

the reference to the 4/19 post along with linked slide shows

An excerpt from Howard Fast's eyewitness account of The Peekskill Riots:

"THE ATTACK STARTS A few minutes after I arrived, a boy came running down from the state road and informed us that the fascists had started the attack and that the road was solidly blocked. All the available boys and men--about 25--ran up to the entrance to the grounds. There we discovered that the double entrance had been blocked, one part with a Legion truck, the other with a stone barricade. As we stood there, the fascists launched their first attack, about 300 of them against our handful. There was a brief melee, in which two of our boys were hurt, quite badly. We noticed now that most of the attackers were heavily liquored up; nor were they teen-age boys, as so many stories reported. Most of them were men between 35 and 50--and one of their leaders was identified as a prominent real estate man of Peekskill. At this point, three sheriffs appeared. They were in plain clothes, with gold badges pinned on. Aside from three other men--who were identified as Justice Department agents, and who stood quietly by--these were the only police we on the inside saw for the next two and a half hours. The three sheriffs argued half-heartedly with the fascists; one of them with sufficient guts could have broken up the thing right there; but all three, in all their actions, were against us and on the side of the fascists. While the sheriffs argued, we formed ourselves into three lines, sending the girls back to the bandstand [leaving the males] stretched across the road, which was embanked at this point. There were exactly 42 of us, and we organized into seven groups of six, with a squad leader for each group. We were about half Negro and half white, half teen-age boys, and half men. We had eight trade unionists among us, four of them merchant seamen. From here on, for the next two hours, we maintained our discipline."

I would say even odds that George Pataki's father was part of that lynch mob Here's the full text of Fast's account and as a rare two for one bonus Here's a slide show I put together consisting of archival images of the concert/riots, some recent pictures of the same site (now a luxury Toll Bros. condo with an adjoing golf course). The sound track is the stirring Pete Seeger/Lee Hays song (not to be confused with Toto's), "Hold The Line"

Posted by David Ballela at 12:20 PM 0 comments

Labels: eugene bullard, military

Saturday, February 2, 2008

The Harlem Hellfighters: The 369th Regiment of WWI

from 11/7/07 from pseudo-intellectualism : from wikipedia:

it's hard to view this in the small frame, but hopefully one gets the gist of the story this remarkable group

Harlem Hellfighters is the popular name for the 369th Infantry Regiment, formerly the 15th New York National Guard Regiment. The unit was also known as The Black Rattlers, in addition to several other nicknames. The 369th Infantry Regiment was known for being the first African-American Regiment during WWI.

The 369th Infantry Regiment was constituted June 2, 1913 in the New York Army National Guard as the 15th New York Infantry Regiment. It was organized on June 29, 1916 at New York City. It was Mustered into Federal service on July 25, 1917 at Camp Whitman , New York. It was drafted into Federal service August 5, 1917. The regiment trained in the New York Area, performed Guard Duty at various locations in New York, and trained more intensely at Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where they experienced significant racism from the local communities, and other units. The 15th Infantry Regiment, NYARNG was Assigned on December 1, 1917 to the 185th Infantry Brigade.

It was commanded by Col. William Hayward, a member of the Union League Club of New York, which sponsored the 369th in the tradition of the 20th U.S. Colored Infantry, which the club had also sponsored in the Civil War.

The 15th Infantry Regiment shipped out from the New York Port of Embarkation on December 27, 1917, and joined its Brigade upon arrival in France, but the unit was relegated to Labor Service duties instead of combat training. The 185th Infantry Brigade was assigned on January 5, 1918 to the 93rd Division

The 15th Infantry Regiment, NYARNG was Reorganized and redesignated March 1, 1918 as the 369th Infantry Regiment, but the unit continued Labor Service duties while it waited the decision as to what to do with the unit.

It was finally decided on April 8, 1918 to assign the unit to the French Army for duration of the United States participation in the war. The men were issued French helmets and brown leather belts and pouches, although they continued to wear their U.S. uniforms. The 369th Infantry Regiment was Relieved May 8, 1918 from assignment to the 185th Infantry Brigade, and went into the trenches as part of the 16th French Division and served continuously to July 3rd. The regiment returned to combat in the Second Battle of the Marne. Later the 369th was reassigned to Gen. Lebouc’s 161st Division in order to participate in the Allied counterattack. On August 19, the regiment went off the line for rest and training of replacements. On September 25, 1918 the 4th French Army went on the offensive in conjunction with the American drive in the Meuse-Argonne. The 369th turned in a good account of itself in heavy fighting, sustaining severe losses. They captured the important village of Sechault. At one point the 369th advanced faster than French troops on their right and left flanks. There was danger of being cut off. By the time the regiment pulled back for reorganization, it had advanced fourteen kilometers through severe German resistance.

In Mid-October the regiment was moved to a quiet sector in the Vosges Mountains, It was there on November 11, the day of the Armistice. Six days later the 369th made its last advance and on November 26, reached the banks of the Rhine river, the first Allied unit to get there.

The regiment was relieved on December 12, 1918 from assignment to the French 161st Division, and returned to the New York Port of Embarkation. It was Demobilized on February 28, 1919 at Camp Upton at Yaphank, New York, and returned to the New York Army National Guard.

During its service the regiment suffered 1500 casualties and took part in the following campaigns:

1. Champagne–Marne

2. Meuse–Argonne

3. Champagne 1918

4. Alsace 1918

One Medal of Honor and many Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded to members of the regiment. The most celebrated man in the 369th was Pvt. Henry Lincoln Johnson. In May 1918 Johnson and Pvt. Needham Roberts fought off a 24-man German patrol, though both were severely wounded. After they expended their ammunition, Roberts used his rifle as a club and Johnson battled with a bolo knife. Johnson was the first American to receive the Croix de Guerre. By the end of the war, 171 members of the 369th were awarded the Legion of Honor.

Photographs show that the 369th carried the New York Regimental flag overseas. The French government awarded the regiment the Croix de Guerre with silver star for the taking of Sechault. It was pinned to the colors by General Lebouc at a ceremony in Germany, December 13, 1918.

One of the first units in the United States armed forces to have African American officers in addition to its all-black enlisted corps, the 369th compiled an astounding war record, earning several unit citations along with many individual decorations for valor from the French government.

The 369th Infantry Regiment was the first New York unit to return to the United States, and was the first unit to march up Fifth Avenue from the Washington Square Park Arch to their Armory in Harlem, and their unit was placed on the permanent list with other veteran units.

In re-capping the story of the 369th Arthur W. Little, who had been a battalion commander, wrote in the regimental history “From Harlem to the Rhine” that it was official that the outfit was 191 days under fire, never lost a foot of ground or had a man taken prisoner, though on two occasions men were captured but they were recovered. Only once did it fail to take its objective and that was due largely to bungling by French artillery support. There were 1500 casualties.

During the war the 369th's regimental band (under the direction of James Reese Europe) became famous throughout Europe, being the first to introduce the until-then unknown music called jazz to British, French and other audiences, and starting a world-wide demand for it.

Notable soldiers

* Sgt. Henry Johnson, winner of the Croix de Guerre

* Spotswood Poles, referred to as "the black Ty Cobb" for his prowess in the Professional Negro Baseball leagues in the early 1900s

* Colonel Hamilton Fish III, Regimental Commander of the 369th Regiment, New York Congressman, author, and Founder of the Order of Lafayette.

Posted by David Ballela at 9:31 PM 0 comments