I found the audio at Bridgewater State University and combined it with images of Cuffee and/or related to him, including the Paul Cuffee School in Providence, Rhode Island. Note some spell his name Cuffee and others Cuffe.

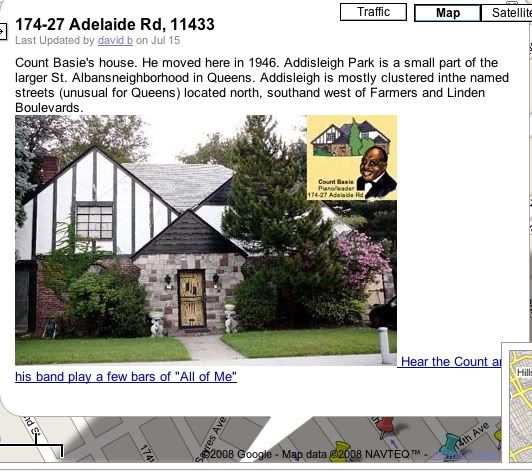

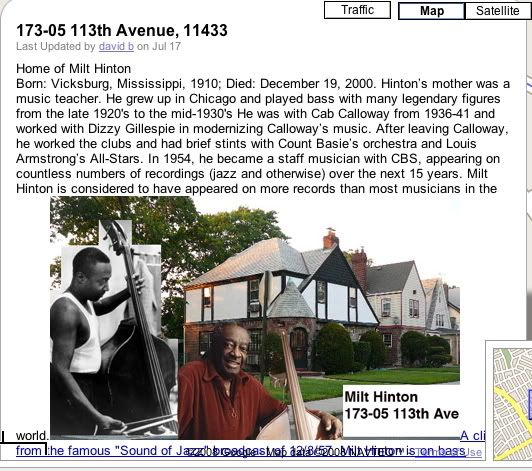

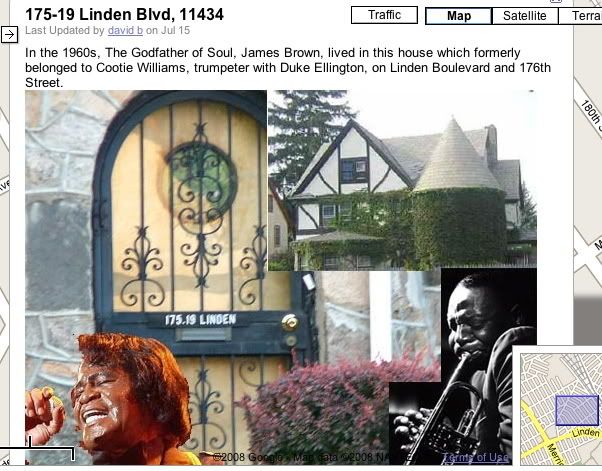

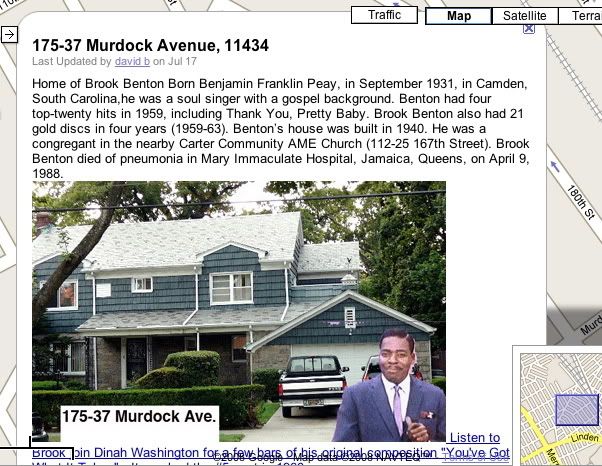

Paul Cuffee, Negro shipowner and colonizer, was born near New Bedford, Massachusetts. As a free Negro whose father had been a slave, Cuffee became greatly concerned over the status of the Negroes in his native state and throughout America to the extent that he became one of the first to advocate African colonization as a solution to the incipient racial problem. In 1811, he traveled to Sierra Leone, a British colony on the West Coast of Africa, where he founded the Friendly Society of Sierra Leone, for the emigration of free Negroes from America. In 1815, he spent $4,000 of his own funds to transport 38 Negroes to Sierra Leone. He had planned more expeditions to Africa, but his health failed and he died in 1817.

A successful shipbuilder and shipowner, he accumulated an estate worth more than $20,000. In 1797, at a price of $3,500, he purchased for himself and his Indian wife, Alice Pequit, a farm on which he built a school for free Negro children. He and his brother, John Cuffee, entered a suit, as taxpayers, against the state of Massachusetts for the right to vote; but they were unsuccessful in winning the case. Several years later, legislation was adopted to correct the unjust practice. The Negro entrepreneur campaigned regularly against discriminatory practices faced by the Negroes in America. His association with whites was unquestioned, and he was received by the Quakers as a member of the Westport Society of Friends.

More on Cuffee

Paul Cuffee (1759—September 9, 1817) is most commonly known for his work in aiding free Negroes who wanted to emigrate to Sierra Leone. With the help of his shipping company Cuffee launched his first expedition to Sierra Leone on January 2, 1811. While in Sierra Leone, Cuffee helped to establish “The Friendly Society of Sierra Leone”, a trading organization. He had faith that the Friendly Society would help to establish a far more powerful Sierra Leone economy as well as self-help projects for the residents of the colony. He envisioned a mass emigration of Negroes to Africa.

Paul Cuffee was born free on Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts, the youngest of ten children. His father, Kofi (also known as Cuffee Slocum and "Cuffee Cuffee"), was a member of a West African Ashanti tribe who had been captured and brought to America as a slave at the age of 10. Paul's mother, Ruth Moses, was a Native American and a member of a local tribe. Kofi was a skilled carpenter who educated himself and earned his freedom. Cuffee's father died when he was a teenager. He and his brothers refused to use the name Slocum, which his father had acquired from his owner, and adopted his father's personal name Hosie Cuffee

The closest mainland port to Cuttyhunk was New Bedford, Massachusetts, the center of the American whaling industry. At the age of 16, Paul Cuffee signed on a whaling ship and later on cargo ships, where he learned navigation. During the American Revolution he was held prisoner by the British for a time. At the age of 21 he refused to pay his taxes because he did not have the right to vote. Cuffee believed that he should not have to pay taxes if he was not being represented. In 1780 he petitioned the council of Bristol County to end taxation without representation. The petition was denied, but it was one of the influences that led the Legislature to grant voting rights to free male citizens of the state in 1783.

Because Cuffee had grown up on an island he developed a lifelong love for the sea. At age 24 he became part owner of a small vessel and married Alice Pequit. She was a member of the same Native American tribe as Cuffee’s mother. The couple settled in Westport, Massachusetts, where they raised their eight children. As Cuffee became more successful he invested in more ships and made a sizable fortune for the day and especially for a Black man of this era. In the 1790s he made his money in cod fishing and smuggling goods from Canada. With his money Cuffee bought a large farm along the Westport River and was able to invest in the expansion of his fleet.

Along with his shipping business Paul Cuffee always had an interest in the demeaning conditions for most Blacks in the American colonies. Cuffee did not live the average life of the Black man in America so he sought ways to help others who had not been as fortunate. Unfortunately most White Americans felt that Blacks were subordinate to Whites. Many Americans agreed with this quote: “To most white men, blacks were members of a despised and innately inferior race.” Although slavery continued, some believed the emigration of free Blacks outside the United States was the easiest and most realistic solution to the race problem in America. This idea translated into Blacks being sent to other parts of the world in order to establish their own societies and rid America of “the Black man problem”. This idea came partly from Thomas Jefferson and other members of American society.

Many previous attempts by White men to colonize Blacks in other parts of the world had failed miserably, including the British attempt to colonize Sierra Leone with free Blacks, criminals, and prostitutes. In 1787 four hundred people departed from Great Britain and headed for Sierra Leone. “The colony was plagued with serious problems from the outset and proved to be a severe disappointment to its London sponsors.”

Although colonizing Sierra Leone was an extremely difficult task, Cuffee believed it was a viable option for Blacks and threw his support behind the movement. Paul Cuffee stated “I have for these many years past felt a lively interest in their behalf, wishing that the inhabitants of the colony might become established in truth, and thereby be instrumental in its promotion amongst our African brethren.” Cuffee received encouragement to proceed with his project from people in New York, Baltimore, and Boston as well as members of the African Institution. Cuffe mulled over on the logistics and chances of success for the movement for three years before deciding in 1809 to move ahead with the proposed project. He launched his first expedition to Sierra Leone on January 2, 1811.

Cuffee reached Freetown, Sierra Leone on March 1, 1811. During his time there he traveled the area investigating the social and economic conditions of the region. He met with some of the colony’s officials, who opposed Cuffee’s idea for colonization of free Blacks from America. Because Cuffee had contacts with powerful officials from the African Institution he sailed to Great Britain to seek help from there.

Surprisingly Cuffee was welcomed in Britain with open arms. He met with the heads of the African Institution and was granted permission to continue with his mission in Sierra Leone. He then left Liverpool and sailed back to Sierra Leone, where he finalized his plans for the colony. While in Sierra Leone, Cuffee helped to establish the Friendly Society of Sierra Leone, a trading organization run by Blacks. He had faith that the Friendly Society would help to establish a far more powerful Sierra Leone economy as well as self-help projects for the residents of the colony. Cuffee’s friends from the African Institution granted the Friendly Society money for these goals. “Heartened by London’s response to the Friendly Society, and also by the evident faith Freetown’s inhabitants entrusted in him, Cuffee now believed the trip to Sierra Leone was well worth the sacrifice of time, effort, and money”. Although Cuffee viewed the expedition as successful, he feared that once he, along with several other powerful leaders, left, the citizens of the colony would again return to their heathen ways. So, Cuffee left the colony with a message advising them how to behave and warned them that they should not defer from his advisement.

After returning to America in 1812, Cuffee was arrested for bringing British cargo into the United States. His brig, the Traveler, was seized as well. He was summoned to Washington, D.C., for violating trade laws, where he met with the President, James Madison. He was warmly welcomed into the White House by the president. Madison later decided that Cuffee was not aware of and did not intentionally violate the national trading policy. Madison questioned Cuffee’s experience and the conditions of Sierra Leone and was eager to learn about Africa and the possibility of further expanding colonization. “Madison evaluated Cuffee’s plans carefully, but rejected them reluctantly.” Madison believed that there would be too many problems in further attempts to colonize Sierra Leone but regarded Cuffee as America’s African authority.

Cuffee intended to return to Sierra Leone once a year but the War of 1812 between the United States and Britain prevented him from doing so. Sierra Leone was still constantly on his mind. “He visited Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York, speaking to groups of free Negroes on the 'favorable' possibilities of the colony. He also urged Negroes to form organizations in these cities to “communicate with each other… and to correspond with the African Institution and with the Friendly Society at Sierra Leone.” He printed a pamphlet about Sierra Leone to inform the general public of his ideas.

In the spring of 1813 Cuffee suffered several monetary losses because of some unprofitable ventures of his ships; one ship never returned. After getting his finances in order he prepared to return to Sierra Leone. The war between the U.S. and Britain continued, so Cuffe decided he would have to convince both countries to ease their restrictions on trading. He was unsuccessful and was forced to wait patiently until the war ended.

He left on December 10, 1815 with 38 Black colonists and arrived in Sierra Leone on February 3, 1816. Cuffee and his emigrants were not greeted as warmly as before. The authorities were already having trouble keeping the general population in order and were not thrilled at the idea that more emigrants were arriving. Although things did not go exactly as planned, Cuffee believed that once continuous trade between America, Britain, and Africa commenced the society would realize his predicted success. Cuffee left Sierra Leone in April filled with optimism for its future.

In 1816 Cuffee’s vision resulted in a mass emigration plan for Blacks. Although Cuffee was a successful Black man he still frequently dealt with discrimination. This time around Congress rejected his petition to return to Sierra Leone. “The year 1816 was one of great racial tension in this country.” During this time period many Black Americans began to demonstrate interest in immigrating to Africa. In 1816 Cuffee was persuaded by Reverends Samuel J. Mills and Robert Finley to help them with their colonization plans in the American Colonization Society. “Unlike the white abolitionists, he failed to take note or deliberately ignored the fact that Colonization Society was concerned only with encouraging free Negroes to emigrate from America, and that its members were not interested in disturbing the status quo in the South.”

In the beginning of 1817 Cuffee’s health deteriorated. He never returned to Africa and died on September 7, 1817.