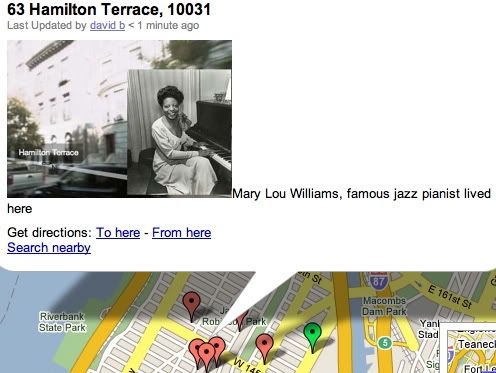

from my google map of harlem

Williams' 63 Hamilton Terrace apartment was famous in the mid-1940s as a salon where she imparted her knowledge of the jazz tradition to cutting-edge musicians.

from Rutgers' biographical site on Mary Lou Williams

"I'm the only living musician that has played all the eras," Mary Lou Williams confidently advised Marian McPartland in the debut 20 years ago of McPartland's acclaimed radio broadcast, Piano Jazz. "Other musicians lived through the eras and they never changed their styles."

She was right. Jazz fans and historians long ago concluded that Mary Lou Williams was the most important female jazz musician to emerge in the first three decades of jazz. William's multidimensional talents as an instrumentalist, arranger, and composer made her a star from her earliest days and, over the long haul, an equal to any musician successful in those endeavors. Her longevity as a top-flight jazz artist was extended because of her penchant for adapting to and influencing stylistic changes in the music.

In his autobiography, Music Is My Mistress, Duke Ellington wrote, "Mary Lou Williams is perpetually contemporary. Her writing and performing have always been a little ahead throughout her career. Her music retains, and maintains, a standard of quality that is timeless. She is like soul on soul."

Indeed, this process of constant reassessment and renewal she applied to her art is but one of the qualities that makes Williams (1910-81) a truly unique figure in the history of jazz. William's range of talents, summed up by what Ellington termed "beyond category," suggests both the richness and the ambiguity that have made assessing her role in jazz history challenging. Through the Williams Collection, researchers can, for the first time, more fully evaluate a pianist who was simultaneously a master of blues, boogie woogie, stride, swing, and be-bop. Her work as a composer and arranger for Andy Kirk's Twelve Clouds of Joy in the early 1930s reveals one of the earliest examples of a woman given due respect from her peers for her musicianship. William's career opens a window into the critically important Kansas City jazz scene that produced such giants as Count Basie, Lester Young, and Charlie Parker. Her stature in the jazz world is a natural attraction for scholars examining the lives not only of women jazz musicians, but also of twentieth-century African-American women and American history in a larger context.

Born Mary Elfrieda Scruggs on May 8, 1910, in Atlanta, Williams grew up in Pittsburgh, where her prodigious talents led to work as a hardscrabble professional traveling musician while still in her early teens. She came to prominence in the early 1930s with Kirk's Twelve Clouds of Joy, a leading southwestern territory swing band. Williams was not only the band's star soloist but also its chief arranger. Beyond the normal obstacles confronting African-Americans in that pre-civil rights era, she also had to contend with a musical milieu in which women instrumentalists were rare and women arranger/composers virtually non-existent. Billed as "The Lady Who Swings the Band," William's playing and writing were on a par with any of her more famous contemporaries. "Outside of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, there's no other composer she has to take a back seat to," David Berger, professor at Manhattan School of Music, told The Washington Post recently. In addition to her work for Andy Kirk, she composed and arranged for leading orchestras of the swing era: Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Benny Goodman. These musical manuscripts are part of the Collection.

With her departure from the Kirk band in 1942, Williams settled in New York, where she opened her Harlem apartment to all types of musicians and was particularly encouraging to the experimentation of the young modernists. She helped to inspire and adapted to the revolutionary new style known as be-bop, which reduced many of her contemporaries to anachronisms, and also mentored many of the movement's founders, including Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker. (She crossed similar stylistic frontiers in 1977 when she performed a Carnegie Hall concert of duets with the avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor.)

Her writing also continued to grow; along with Duke Ellington, she was a pioneer among jazz composers in producing extended works, such as the Zodiac Suite. In 1945, she debuted segments of the Suite on her weekly radio broadcast, Mary Lou Williams Piano Workshop, and performed three movements with the 70-piece New York Pops Orchestra during the June 1946 Carnegie Hall Pops Series. William's tours of England in 1952 and France in 1952, both widely covered in the European jazz press, place her in the tradition of Armstrong and Ellington two decades earlier in spreading jazz on the Continent.

In 1956, Williams underwent a spiritual conversion to Catholicism and gave up playing to concentrate on spiritual matters until reemerging in 1957 with a performance alongside Dizzy Gillespie at the Newport Jazz Festival. Compared to her rigorous schedule of touring over the previous 30 years, she played only sporadically over the next decade. She formed the Bel Canto Foundation to assist drug- and alcohol-dependent musicians in 1958. This initiative prefigured her founding of Cecilia Music, a publishing firm to release her compositions, and the establishment of Mary Records to issue her and other selected artists' recordings. Both of these events occurred in the early 1960s, when she also issued one of her later noteworthy recordings, the 1963 Mary Lou Williams Presents St. Martin de Porres.

Williams undertook several ambitious extended works during this period, including her 1971 composition Mary Lou's Mass, which was choreographed by Alvin Ailey and, in 1975, was performed during celebration of a Mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral. In 1977, her career undertook yet another significant turn. Duke University formalized William's role as an educator by appointing her as artist-in-residence, a position she held until her death in 1981. Duke permanently honored William's contributions by opening the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture in September 1983 with an address by Nobel Prize winning author Toni Morrison.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment