Monday, February 25, 2008

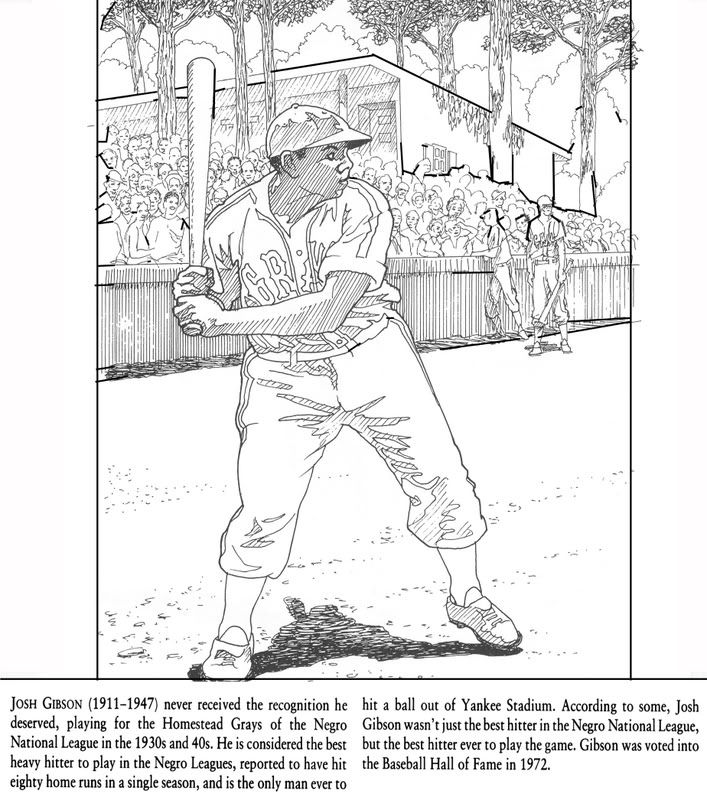

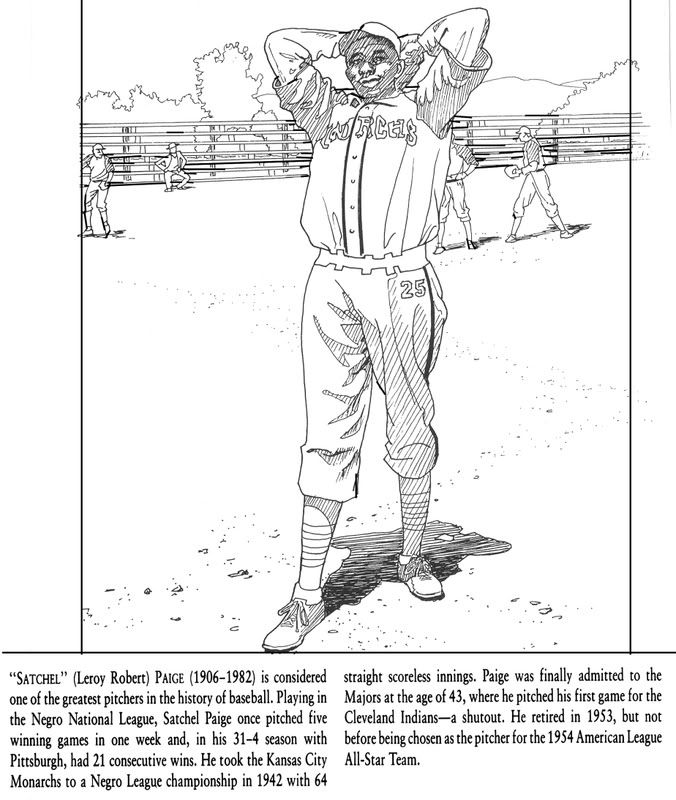

Black History Coloring Pages: Josh Gibson And Satchel Paige

Posted by David Ballela at 5:44 PM 0 comments

Labels: coloring pages, josh gibson, satchel paige

Friday, February 22, 2008

Josh Gibson: A Biography

Joshua Gibson (December 21, 1911 - January 20, 1947) was an American catcher in baseball's Negro Leagues. He played for the Homestead Grays from 1930 to 1931, moved to the Pittsburgh Crawfords from 1932 to 1936, and returned to the Grays from 1937 to 1939 and 1942 to 1946. In 1937 he played for Ciudad Trujillo in Trujillo's Dominican League and from 1940 to 1941 he played in the Mexican League for Veracruz. He stood 6-foot-1 (185 cm) and weighed 210 pounds (95 kg) at the peak of his career.

Baseball historians consider Gibson to be among the very best catchers and power hitters in the history of any league, including the Major Leagues, and he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972. Gibson was known as the "black Babe Ruth." He never played in Major League Baseball because, under their unwritten "gentleman's agreement" policy, they excluded non-whites during his lifetime.

Gibson was born in Buena Vista, Georgia on or about December 21, 1911. In 1923 Gibson moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where his father, Mark Gibson, had found work at the Carnegie-Illinois Steel Company. Entering sixth grade in Pittsburgh, Gibson prepared to become an electrician, attending Allegheny Pre-Vocational School and Conroy Pre-Vocational School. His first experience playing baseball for an organized team came at age 16, when he played third base for an amateur team sponsored by Gimbels department store, where he found work as an elevator operator. Shortly thereafter, he was recruited by the Pittsburgh Crawfords, which in 1928 were still a semi-professional team. The Crawfords, controlled by Gus Greenlee, were the top black semi-professional team in the Pittsburgh area and would advance to fully professional major Negro league status by 1931.[3]

In 1928, Gibson met Helen Mason, whom he married on March 7, 1929. When not playing baseball, Gibson continued to work at Gimbels, having given up on his plans to become an electrician to pursue a baseball career. In the summer of 1930, the 18-year old Gibson was recruited by Cum Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays, which were the preeminent Negro league team in Pittsburgh, and on July 31, 1930 Gibson debuted with the Grays. A few days later, on August 11, 1930, Gibson's wife Helen, who was pregnant with twins, went into premature labor and died while giving birth to a twin son, Josh Gibson, Jr., and daughter, named Helen after her mother. The children were raised by Helen's parents.

The Negro leagues generally found it more profitable to schedule relatively few league games and allow the teams to earn extra money through barnstorming against semi-professional and other non-league teams.[4] Thus, it is important to distinguish between records against all competition and records in league games only. For example, against all levels of competition Gibson hit 69 home runs in 1934; the same year in league games he hit 11 home runs in 52 games.

In 1933 he hit .467 with 55 home runs in 137 games against all levels of competition. His lifetime batting average is said to be higher than .350, with other sources putting it as high as .384, the best in Negro League history.

The Josh Gibson Baseball Hall of Fame plaque says he hit "almost 800" homers in his 17-year career against Negro League and independent baseball. His lifetime batting average, according to the Hall of Fame's official data, was .359.[4] It was reported that he won nine home-run titles and four batting championships playing for the Crawfords and the Homestead Grays. In two seasons in the late 1930s, it was written that not only did he hit higher than .400, but his slugging percentage was above 1.000. The Sporting News of June 3, 1967 credits Gibson with a home run in a Negro League game at Yankee Stadium that struck two feet from the top of the wall circling the center field bleachers, about 580 feet from home plate. Although it has never been conclusively proven, Chicago American Giants infielder Jack Marshall said Gibson slugged one over the third deck next to the left field bullpen in 1934 for the only fair ball hit out of Yankee Stadium.

There is no published season-by-season breakdown of Gibson's home run totals in all the games he played in various leagues and exhibitions.

The true statistical achievements of Negro League players may be impossible to know, as the Negro Leagues did not compile complete statistics or game summaries. Based on research of historical accounts performed for the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues, Gibson hit 224 homers in 2,375 at-bats against top black teams, 2 in 56 at-bats against white major-league pitchers and 44 in 450 AB in the Mexican League. John Holway lists Gibson with the same home run totals and a .351 career average, plus 21 for 56 against white major-league pitchers. According to Holway, Gibson ranks third all-time in the Negro Leagues in average among players with 2,000+ AB (trailing Jud Wilson by 3 points and John Beckwith by one. Holway lists him as being second to Mule Suttles in homers, though the all-time leader in HR/AB by a considerable margin - with a homer every 10.6 AB to one every 13.6 for runner-up Suttles.

Recent investigations into Negro League statistics, using box scores from newspapers from across the United States, have led to the estimate that, although as many as two thirds of Negro League team games were played against inferior competition (as traveling exhibition games), Josh Gibson still hit between 150 and 200 home runs in official Negro League games. Though this number appears very conservative next to the statements of "almost 800" to 1000 home runs, this research also credits Gibson with a rate of one home-run every 15.9 at bats, which compares favorably with the rates of the top nine home-run hitters in Major League history. The commonly-cited home run totals in excess of 800 are not indicative of his career total in "official" games because the Negro League season was significantly shorter than the major league season; typically consisting of less than 60 games per year. [6] The additional home runs cited were most likely accomplished in "unofficial" games against local and non-Negro League competition of varying strengths, including the oft-cited "barnstorming" competitions. Though these numbers are still based on incomplete evidence, this study does at least provide concrete proof that Josh Gibson was a power hitter of very high caliber.

Despite the fact that statistical validation continues to prove difficult for Negro League players, the lack of verifiable figures has led to various amusing "Tall Tales" about immortals such as Gibson.[7] A good example: In the last of the ninth at Pittsburgh, down a run, with a runner on base and two outs, Gibson hits one high and deep, so far into the twilight sky that it disappears from sight, apparently winning the game. The next day, the same two teams are playing again, now in Washington. Just as the teams have positioned themselves on the field, a ball comes falling out of the sky and a Washington outfielder grabs it. The umpire yells to Gibson, "You're out! In Pittsburgh, yesterday!"

In early 1943, Josh Gibson fell into a coma and was diagnosed with a brain tumor. Apparently coming out of his coma, he refused the option of surgical removal, and lived the next four years with recurring headaches. Gibson died of a stroke in 1947 at age 35, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, just three months before Jackie Robinson became the first black player in modern major league history. The stroke is believed by a few to be linked to drug problems that plagued his later years. He was buried at the Allegheny Cemetery in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Lawrenceville, where he lay in an unmarked grave until a small plaque was placed in 1975.

In 2007 the Washington Nationals decided to honor Josh Gibson as one of the "greatest players to play baseball in Washington, D.C." with a statue as part of their new baseball stadium in Southeast DC. The statue is to be dedicated sometime in 2008.

His son Josh Gibson, Jr. played baseball for the Homestead Grays. His son was also instrumental in the forming of the Josh Gibson Foundation

Posted by David Ballela at 9:14 AM 0 comments

Labels: baseball, josh gibson, negro leagues

We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball, By Kadir Nelson

I bought this book recently. A great story and the illustrations are incredible.

The audio is from an NPR broadcast of 1/29/08 . The first four images in the slide show are from the book, then there's a grouping of Josh Gibson and finally an assortment of Negro League memorabilia

The vivid, detailed and realistic pictures in a new book for children transport readers to the past and the world of baseball's Negro Leagues.

Award-winning artist Kadir Nelson wrote and illustrated the book, We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball, which is his first as an author.

The project took Nelson nearly eight years to complete.

"It started off as a few paintings and then it grew into more than 40 paintings," Nelson tells Michele Norris.

Each painting required a tremendous amount of research. Nelson read a number of books about the Negro Leagues and interviewed former players, including Walt McCoy, who lives in San Diego, as does Nelson.

"It helps a lot to hear the history directly from someone who lived it, rather than reading it in a textbook," Nelson says.

"I felt that if I [wrote the book] in that way — like a grandfather telling his story to his grandchildren — it would make the history all the more real," he says.

Nelson describes how the men and women who played in the Negro Leagues — faced with discrimination and a ban against their playing in the Major Leagues — created their own "grand stage" to showcase their talents.

It was characterized by rough-and-tumble play; Nelson notes that Negro League players threw pitches that were banned in the Major Leagues and, as a result, learned how to hit anything.

"By the time integration came, when Jackie Robinson crossed the color barrier in 1947, African-American ballplayers were prepared to hit anything and to play at that high level of play," Nelson says.

The title of the book comes from a quote from the founder of the Negro Leagues, Rube Foster: "We are the ship, all else the sea."

Nelson says it was a "declaration of independence" of the Negro Leagues from the Major Leagues — and a fitting title for his book.

"This story is presented in the first-person plural. We played baseball. This is how we lived, and this is what we did to enable African Americans and people of color to follow in our footsteps."

an excerpt

"It was a rough life — ride, ride, ride, and ride." — Hilton Smith, pitcher

We played in a rough league. We had a number of really unsavory characters like Charleston or Jud Wilson to contend with, as well as pitchers who didn't have a problem throwing at us, but that was something we had accepted as part of the game. I think what made our time a bit harder than most is what we had to deal with in addition to that. White fans would call us names and throw stuff at us on the field, and we couldn't say a word. In some places we traveled to, we couldn't get a glass of water to drink, even if we had money to pay for it — and back then, water was free!

We did an awful lot of traveling, mostly in buses. They were nice buses to begin with, but they weren't the kind that were made for ridin' every day. We ran those poor buses ragged. Many a time we'd ride all day and night and arrive just in time to play a game. Then we'd get back on that hot bus and travel to the next town for another game, often without being able to take a bath. This was all season long. All of that traveling would wear on you. Many times the only sleep we got was on the bus. But that could be hard because we had to take the back roads to get to some of those little towns, and they were so bumpy they'd have us bouncing around the bus like popcorn on a hot stove. Fastest we could go was about thirty-five to forty miles an hour. If the driver got sleepy, a couple of the guys on the team would take turns driving the bus. To pass the time we played cards or sang old Negro spirituals or barbershop numbers. Just about every team had a quartet. They'd be our entertainment for most of the way. Some guys could really sing. Most people don't know it, but Satchel Paige had a wonderful singing voice, and so did Buck Leonard. We would listen to them and try to join in.

Traveling was even rougher down South. They didn't take too kindly to black folks down there — especially if you were from up north. We would have to travel several hundred miles without stopping because we couldn't find a place where we could eat along the way. It's a hurtful thing when you're starving and have a pocket full of money but can't find a place to eat because they "don't serve Negroes." And you could forget about trying to use the restroom in those places. You would just have to hold it, or stop the bus and do your business in the woods. We had to get used to it. After a while, we learned which places we could stop at and which ones we couldn't. They didn't have any fast-food places back then. Many times we wouldn't get food to eat before a game, and if we did, it usually wasn't much. We would have to play a doubleheader on only two hot dogs and a soda pop. If we couldn't buy food from a restaurant or a hot dog stand, we'd stop at a grocery store and get some sandwiches or sardines and crackers. Sometimes those grocery store clerks didn't want to serve us, either. One time a store clerk told us to put our money in an ashtray if we wanted to buy something. He grabbed the money out of the ashtray and put the change back in it. He didn't want to touch our hands, but he sure did touch that money. I guess he had to draw the line somewhere. Just didn't make any sense.

It was segregated in the North, too. They wouldn't serve us inside a restaurant, so we had to get our food from the back door and eat on the bus. We'd send one guy to buy food for the whole team. Hotels were segregated, too. Many times we would get to a town after riding all day, only to spend a few more hours searching for a place to stay. The minute we arrived, inexplicably, every hotel would be full. If we couldn't find anyplace to stay, we would have to sleep on the bus.

Some of the smaller clubs slept crammed in their cars or even in the ballpark because they couldn't afford to stay in a hotel. Some teams slept at the YMCA, the local jail, even in funeral homes. In cities, we stayed in Negro hotels or Negro rooming houses. We slept two, three guys to a bed. That's all the team owner could afford. A number of the Negro hotels were very clean and neat. But more than a few times, we'd run into those places — and I won't call out any names — that had so many bedbugs you'd have to put a newspaper between the mattress and the sheets. And then in other places, we had to sleep with the lights on because the bedbugs would crawl all over you when the lights were out. Can't sleep with a bug on your leg — I don't care how tough you are.

In small towns we'd stay with local families. During the game, the manager would send someone to find people who would put us up for the night. By the time the game was over, we all had places to stay. Sometimes the colored church would fix us a meal, and I'll tell you, that was some good eating. If we got to a town and we had a little time to kill, we'd go fishing or catch a movie. Back then, a movie ticket only cost about twenty-five cents, and you could stay in the theater all day if you wanted to. We had to go through the back entrance, though, because they only allowed Negroes to sit in the balcony. There would usually be three levels in the theater, and the white audience would sit at the bottom. That whole middle section would be empty, as if the owners wanted us to be as far away from the white audience as possible. That kind of thing seems silly today, but that's how it was back then.

From WE ARE THE SHIP: THE STORY OF NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL by Kadir Nelson. Text and illustrations copyright (c) 2008 by Kadir Nelson. Rerinted by permission of Hyperion Books for Children. All rights reserved.

Posted by David Ballela at 8:53 AM 0 comments

Labels: book recommendations, josh gibson, negro leagues

Josh Gibson

The folks at brooklynblowback provide a great service in posting read aloud videos on youtube. Here's one they did of the book, "Just Like Josh Gibson," by Angela Johnson

from amazon

Kindergarten-Grade 3--A young narrator opens this story about her grandmother with an anecdote about the legendary Josh Gibson, a Negro League player who once hit a baseball so hard in Pittsburgh that it landed during his game in Philadelphia the next day. That was the day Grandmama was born. Her father brought a Louisville slugger to the hospital and vowed that his daughter would "make baseballs fly, just like Josh Gibson." She became as good a player as the boys on the Maple Grove All-Stars, and sometimes she was invited to practice with them. When her cousin hurt his arm during a game, Grandmama got her chance to hear the cheers as she ran the bases, "stealing home." Peck's well-designed, richly colored pastel artwork, which shows people with emotion and depth, is clearly the highlight of the book. Young Grandmama, in yellow pedal pushers or a pink dress, stands out among the boys' white uniforms and the burnt orange chest protectors of the catcher and umpire. A close-up at the end shows the narrator holding the very ball her grandmother hit, as the older woman looks on, her hand on a photo of the team. Information about Hall of Famer Gibson is appended. Although the story is slight, it imparts the message that a girl can succeed at a "boy's game" if she sets her mind to it.

Posted by David Ballela at 7:03 AM 0 comments

Labels: baseball, book recommendations, josh gibson, negro leagues

Bingo Long And The Traveling All Stars And Motor Kings

about the Negro Leagues from teacher vision, written for the 75 year commemorative year anniversary of the

Negro Leagues

Negro League Baseball

The Negro Leagues Commemorative Year

Have you ever heard of Oscar Charleston — does his name ring a bell at all? He's recognized by some as one of the most talented baseball players of all time. His career has been compared to both Ty Cobb's and Babe Ruth's. In 1921, he batted .430 and led the league in doubles, triples and home runs. He retired with a .376 batting average, and in 1976 was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Yet sadly, the answer to the question just asked is probably "no" — because Charleston played at a time when blacks weren't allowed to play in the "white" major leagues. He is just one of literally thousands of exceptional ball players that segregation robbed of the recognition and the opportunities they richly deserved.

The Early Stages

In May, 1878, John "Bud" Fowler became the first black player to play professionally, albeit in the minors, when he took the mound for the Lynn Live Oaks of the International League. Throughout the 1880's, despite a prevalence of segregation, many black players suited up for minor league teams and finally in 1884, Moses "Fleetwood" Walker became the first black baseball player to reach the majors when his Toledo Blue Stockings joined the majors' American Association. Unfortunately it was short-lived, as the team could not survive financially and folded after the 1884 season. The talent exhibited by Walker and the other black players was unquestioned ,and according to reports, began to scare white players who felt that their jobs might be in jeopardy. Black players were greeted more and more with "Whites Only" signs on locker room doors, and by the late 1880s, the color barrier was in full effect.

The first all-black team was put together in 1885 and was for a short time known as the "Argyle Athletics." They toured the Northeast, often playing the best white teams in the area, but were usually met with resistance from white fans. With hopes of attracting more white fans to the games, team owner Walter Cook attempted to fool them by changing the name of the team to the Cuban Giants. Players were even instructed to avoid speaking English while in public and on the field. The scheme worked for a while but by the turn of the century, no black players or teams were allowed to play with whites.

"If this ain't the big leagues, there ain't no such thing!"

—Slim Jones,

Pitcher, Philadelphia Stars

Despite this fact, Negro League Baseball began to flourish. Several immensely talented leagues formed, most with very loyal fan bases. In 1908, Andrew "Rube" Foster, star pitcher and owner of the Leland Giants in Chicago, finally orchestrated a desegregated three-game series between his team and the Chicago Cubs of the National League. Played at Comiskey Park in front of huge crowds, the Cubs won all three games — but closely, proving the relative equality of talent on the two teams. Over the next decade, Negro League teams played over fifty games with Major League teams, winning more than they lost.

In 1919, Foster pleaded with Major League commissioner Kennesaw "Mountain" Landis to allow a black team into the majors, citing the obvious increased revenues from thousands of black baseball fans. He was ultimately denied and formed his own black major league — the Negro National League. In 1923, the Eastern Colored League was formed, and in 1924, the champions of both leagues met in the first Negro World Series. Both leagues succeeded throughout the roaring '20s but by 1931, after Foster's death and in the midst of the Great Depression, were wiped out.

Not Just Clowning Around

During the 1930s, again with hopes of attracting white fans, black baseball games were often coupled with singing, dancing and comedy skits. The Ethiopian Clowns toured the south, playing their games with their hats on sideways and their faces painted like African tribesmen. The Zulu Cannibal Giants took it a step further. Not only did they paint their faces but they wore grass skirts, used bats resembling African war clubs and often played in bare feet. Underneath the paint and the ridiculous getups were some of the best athletes of that era. Negro League legends David Barnhill and Buck O'Neil were members of the Clowns, and the team's legitimacy was proven in 1941 when it joined the established Negro American League. In 1933, Negro League baseball finally got the financial support it needed to show off its superior brand of baseball... albeit from shady sources. Bar owner Gus Greenlee, known for his involvement in gambling and racketeering, raided teams throughout the country and formed a league of his own that showcased top players. The league was again called the Negro National League and featured the Pittsburgh Crawfords, whose members included future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, and pitcher Satchel Paige.

Satchel Paige, credited with 55 no-hitters, was the first Negro League star to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Negro League records are widely incomplete, but the 6'1", 210 pound Gibson's accomplishments are legendary. He is considered the first and only player to hit the ball completely out of Yankee Stadium. Though he didn't always bat against professional pitching, he is credited with hitting 75 home runs in 1931, 69 in 1934, 84 in 1936 and 962 over his entire career. As a catcher for the Homestead Grays, he combined with fellow Hall of Famer Buck Leonard to form the "Thunder Twins," the black version of Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Satchel Paige, ace of the Crawfords, was perhaps the most colorful player of the era. Brimming with confidence, he used to send his entire infield into the dugout when the opposing team's best hitter stepped to the plate. He reportedly played over 2,000 games in the '20s and '30s.

Cool Papa Bell is one of the most dangerous hitters and undoubtedly the fastest base runner the Negro Leagues had ever seen. His speed lent itself to unending "fish" stories, most notably one that had Bell hitting a ground ball up the middle that hit him while sliding into second.

Jackie Robinson

Robinson wasn't the most talented player in the Negro Leagues, but Rickey considered him the most "suitable" player to desegregate baseball. The fact that he was married —and wouldn't give white ballplayers the impression that he would pursue their girlfriends— and his time in the Army and in school made him the top choice.

Over 20,000 fans filed into Comiskey Park to watch the Negro National League All-Star Game in 1933. By 1937, a sister league, the Negro American League, was formed. Thanks to the respect and popularity of these players and many like them, the leagues prospered in the '30s and well into the 1940s, when the color barrier was finally broken. Jackie Robinson had already spent time in the U.S. Army and been a four-sport star at UCLA when Branch Rickey, owner of the Major League's Brooklyn Dodgers, spotted him playing with the Kansas City Monarchs. Robinson wasn't the most talented player the Negro Leagues had to offer, but Rickey considered him the most "suitable" player to desegregate baseball. The fact that he was married (and therefore wouldn't give white ballplayers the impression that he would pursue their white girlfriends) and his time spent interacting with whites in the Army and in school made him Rickey's top choice. When he signed him to a minor league contract in 1945, Rickey told Robinson he was "looking for a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back." He imposed a two-year commitment to silence, which Robinson grudgingly agreed to.

He played one season in the minors with the Montreal Royals and led the team to a league championship while leading the league in batting. The racial taunts were endless, but he stayed silent. On April 15, 1947, despite a petition by several of his teammates refusing to play, Jackie Robinson made his major league debut.

He played the entire season for the Dodgers, leading the league in steals and winning the Rookie of the Year award. Three months later, Larry Doby became the first black player in the American League when he was signed by the Cleveland Indians. Paige was signed by the Indians in 1948, becoming the oldest rookie ever. He only had twenty more years of playing left in him. Robinson won the league MVP in 1949 and teammate Roy Campanella, the Majors' first black catcher, later won it three more times. Some were still hesitant and racial threats persisted, but for all intents and purposes, the barrier was broken.

Today

Baseball has come a long way in the last fifty years towards recognizing the thousands of black players that lost opportunities. In 1997, as part of the 50th anniversary of the integration, Robinson's No. 42 was retired by every major league team. Currently 16 Negro League players are members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the Negro Leagues now have their own museum in Kansas City. But as Paige said himself, "There were many Satchels, many Josh's." Hank Aaron is the all-time home run king, Willie Mays dazzled in the 50's and 60's, and black players such as Ken Griffey, Jr., Barry Bonds and Mo Vaughn are some of the top players in baseball today. We'd be naive to think the same couldn't have been true in the 1920s, '30s and '40s.

Posted by David Ballela at 1:22 AM 2 comments

Labels: baseball, josh gibson, movies, negro leagues, satchel paige