This is Illinois in the 1940's

from a great resource on swing music history

Although Illinois Jacquet may be best remembered as the tenor saxophonist who defined the screeching style of playing the instrument, his warm and sensitive tone may also be heard on countless jazz ballads and medium groove-tempo numbers since the mid 1940s.

Illinois Jacquet was born Jean-Baptiste Jacquet October 31st, 1922 in Broussard, Louisiana. His mother was a Sioux Indian and his father, Gilbert Jacquet, was a French-Creole railroad worker and part-time musician.

The nickname Illinois came from the Indian word "Illiniwek," which means superior men. He dropped the name Jean-Baptiste when the family moved from Louisiana to Houston because there were so few French-speaking people there.

Jacquet, one of six children, began performing at age 3, tap dancing to the sounds of his father's band. He later played the drums in the Gilbert Jacquet band but discovered his true talent when a music teacher introduced him to the saxophone.

Illinois Jacquet cut his first sides as tenor man with Lionel Hampton's newly formed big band in December of 1941. Six months later and not even lead tenor man in the Hampton big band, his energetic vibraphone playing boss asked him to supply some high-spirited blowing on a tune called Flying Home. By the time Jacquet�s work on the May 26th, 1942 recording was through, he had recorded a unique solo that would follow him a lifetime and make his career.

Years later, during an interview with Nancy Wilson on NPR�s Jazz Profiles, Jacquet explained that when he found out he would be soloing on the record he became worried about how to handle the job. When he voiced his fear to the section leader, his advice was to "play your style." It was sound advice but posed a problem in itself because at that time Illinois had yet to develop a style of his own. Later giving credit for thesolo to divine inspiration he said, "Something was with me at that moment. It all came together for some reason."

Unfortunately the recording ban of 1942 was only months away. On August 1st, 1942 only vocalists were allowed to be recorded on record per a rule laid down by James Petrillo, the head of the American Federation Of Musicians union.

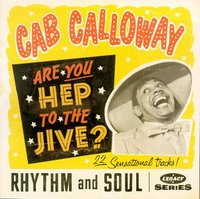

With the recording ban still in place in 1943, Jacquet accepted an offer from Cab Calloway to join his band. Calloway was known to take good care of his musicians financially and although he had big shoes to fill, Illinois jumped at the chance. He was to replace one of his early idols, the phenomenal tenor man Chu Berry, who had recently lost his life in an automobile accident on the way to a Calloway outing in Northern Ohio.

Almost immediately Jacquet found himself in the middle of doing a film soundtrack with Calloway and Lena Horne for the film Stormy Weather. Although he can be seen on screen in the movie he did not solo for the film. Unfortunately due to the recording ban, Jacquet can only be heard soloing with Calloway on live broadcast transcription recordings during his short stay with the band. One of the cleanest sounding surviving examples is on a barn-burning tune called 105 In The Shade.

After leaving the Calloway aggregation Jacquet returned back to his home in Houston where his brother, trumpet man Russell Jacquet, had just broken up his own band. Anxious to move forward in their careers the two traveled to Los Angeles and Illinois began participating in small club "jam sessions" organized by jazz impresario Norman Granz.

When Granz moved jazz to the concert hall with a benefit concert given on behalf of several Mexican kids arrested under questionable circumstances during the Zoot Suit Riots, Jacquet was in the lineup. The tenor master�s screech and honk style was in full swing for the July 2nd, 1944 date considered the first ever Jazz At The Philharmonic concert. Jacquet was a crowd exciter on songs like Blues (my naughty sweetie gives to me) captured in Los Angeles that day. The concert was recorded onto 16" transcription discs and subsequently the performances, which ran well longer than the 3 minutes that would fit on one side of a 78RPM record, were broken up into 3 and 4 sides for public consumption. With Jacquet on the date were Nat Cole, Les Paul, J.J. Johnson, Jack McVea, Shorty Sherock, Johnny Miller, Red Callender, and Lee Young.

The following month Jacquet participated with fellow tenor man Lester Young in a classic short film feature that was nominated for an Academy Award called Jammin' The Blues. Young and Jacquet were both noted for their pork pie hats as much as for their innovative styles on tenor sax.

It was also while in Los Angeles that Jacquet first guested with the Count Basie orchestra, in September of 1944, for an AFRS Jubilee show broadcast. Transcriptions of these performances, now available on a HEP records CD release, find Jacquet blowing in fine fashion on songs like Rock-A-Bye-Basie alongside, Basie tenor man, Buddy Tate.

In November Illinois was part of a studio band that helped back Lena Horne on four sides cut for RCA Victor. It was one of the few instances of Jacquet providing backing for a vocalist in the studio. Ella Fitzgerald, Cora Lee Day and Johnny Hartman were the only other vocalists to release studio recordings with his backing although Billie Holiday was the featured vocalist on many JATP concerts subsequently released on Clef and later Verve.

Jacquet joined the Count Basie big band in earnest in 1945 just after the end of WWII. He remained with Basie until the fall of 1946. He can be heard on many of the Count�s Columbia releases like Mutton Leg, The King, Stay Cool and others. After a lot of soul searching and a good deal of trepidation he left the Count in August of 1946 to join Granz�s JATP which was by this time touring the country.

Illinois Jacquet is credited with recording more than 300 original compositions. Although he was working for Basie, then Norman Granz's Jazz At The Philhamonic, and moonlighting on other sessions, many of his tunes were conceived during the period of his career between 1945 and 1951.

Jacquet's wildly swinging improvisational forays were clearly pleasing live crowds at Jazz At The Philharmonic shows, many of which were being recorded and released on Granz's newly formed Clef record label. But there was also emerging a sensitive and swinging, softer tone on a number of studio recordings for other labels. On a Capitol all-star type session led by guitarist Al Casey on January 19th, 1945, Jacquet handled his parts in a much more subtle style. This soft and swinging, yet deep and robust, phraseology is also evident on sides cut the same day under drummer Sid Catlett�s name.

These more mellow performances set the stage for later 1940s recordings with self-led groups that cut numerous sides for a variety of labels including Apollo, Aladdin, Coral, Decca, and RCA. Robbin�s Nest and Black Velvet were both co-written and recorded by Jacquet in the late 1940s. Both songs became big hits, the former achieving jazz standard status.

Jacquet's success as a leader prompted him to ask Norman Granz for more money in 1948. However the amount Jacquet was asking was more than Granz could afford to pay. Jacquet and Granz parted ways (for the moment) with Illinois concentrating on his own band, which he led with various personnel changes until 1950.

In 1951 Jacquet signed a recording contract with Norman Granz and his Clef record label. This led to once again touring with Granz's Jazz At The Philharmonic. Under the Clef and later Verve banners Jacquet cut some superb studio sides with numerous small groups over the next seven-year period. Some of the greatest jazz stars of all time were recorded with Jacquet like old acquaintances Sweets Edison and Count Basie, Hank Jones and Art Blakey, Roy Eldridge and Ray Brown, Wild Bill Davis, Kenny Burrell, Ben Webster and others.

From 1958 through the 1960s Illinois recorded for a number of labels including Epic, Cadet, Argo, and Prestige.

In the 1970s he can be heard on several European labels including Black Lion, Black And Blue and others.

In 1983 Jacquet was invited to speak at Harvard University. The success of his lecture earned him a return for two semesters as an artist-in-residence. He was the first jazz player ever to serve a long-term residency at the Ivy League school. This inspired him to form another big band, which eventually toured Europe, drawing record crowds.

Jacquet played C-Jam Blues with former President Bill Clinton, an amateur saxophonist, on the White House lawn during Clinton's inaugural ball in January 1993. He also performed for Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

In 1998 Jacquet recorded with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra playing an incredible passage at 76 years of age on Ben Webster�s former signature song with the Ellington band called Cottontail. In so doing he gave away another one of his early influences, the tenor man known by Ellington�s people as Frog.

His last engagement was July 16, 2004 when he led his band at Lincoln Center in New York City.

Illinois Jacquet's flashy playing, which worked countless crowds into a frenzy throughout his career, will likely be what the tenor great is remembered by most. However true jazz and swing fans will also take into account his numerous sides done at slower tempi that communicate the sensitive side of the last of the big toned swing tenor saxophonists.

Illinois Jacquet died Thursday July 22, 2004 of a heart attack. Despite his fame and wealth he lived in a modest home in New York City�s borough of Queens. He was 81.